Researching the various theories of which desert route the ancient Hebrews may have taken out of Egypt into the Land of Canaan in the biblical Exodus story – the geography of which has captivated scholars since the 19th century – brings up images of so many maps with so many routes, it is enough to leave a geo-directionally challenged writer’s head spinning.

Dotted lines and arrows crisscross the maps to locations mentioned in the Bible, some touting a northern route via the Negev Desert, while others show a southern route through the Sinai Desert. All are proposed by scholars and would-be researchers who cannot cite one piece of hard, physical, archaeological evidence indicating that the crossing of a large group of people and animals through the desert ever actually occurred.

In fact, most archaeologists agree that such a journey as described in the Bible never took place.

What are the proposed routes of the biblical Exodus?

Nevertheless, many routes have been suggested over the centuries by pilgrims and scholars – beginning with fourth-century CE Christian historian Eusebius, who set Mount Sinai in the biblical Land of Midian whose borders are not known, through to 16th-century Jews producing maps showing the Exodus to the Promised Land.

These maps included a 1695 map created for the Amsterdam Bible by Abraham Bar Yaakov, a Protestant priest from Germany who converted to Judaism and worked as an engraver in Amsterdam. This map is now in the collection of the National Library of Israel, along with other ancient illustrated maps tracing this epic – and some modern-day scholars would say mythological – journey of the ancient Israelites through the wilderness.

The map of the Exodus added to the Book of Numbers in a Bible published by Richard Harrison in London in 1562, showing the theoretical route the Israelites followed through the wilderness – including the 42 stops along the way – is also included in this collection.

Though differing in style and artistic rendering, the maps share one thing in common with the more contemporary maps scholars and theologians have drawn up since the 19th century: They are all based solely on analysis and comparison of biblical text.

True, of the several dozen places mentioned in the Bible as being along the path taken, the first places – Pithom, Ramses, Migdol and Succoth – are easily identifiable west of the Suez Canal because in many cases, the Arabic names still preserve the connection. And yes, there is a general agreement also about the northeastern part of the Nile Delta probably being where the land of Goshen was located.

And yet, nothing has been found to confirm the biblical account.

“The Israelites may have gone through all the Northeastern Delta, but the types of cultures that leave archaeological remnants are settled cultures where the buildings are made of stone. Nomads do not leave a lot of traces. There is really no ‘wow’ or ‘grab you’ kind of evidence.”

Joshua Berman

“The Israelites may have gone through all the Northeastern Delta, but the types of cultures that leave archaeological remnants are settled cultures where the buildings are made of stone. Nomads do not leave a lot of traces,” said Orthodox rabbi and professor Joshua Berman of Bar-Ilan University’s Bible Studies Department. “There is really no ‘wow’ or ‘grab you’ kind of evidence.”

While perhaps an interesting academic exercise, knowing the exact route taken by the ancient Israelites does not excite him, he said, even having just returned from one of his study tours to Egypt.

“I don’t think that has any effect on the significance of the story,” said Berman. “Exodus is the most often mentioned event in teaching the foundation of our relationship with God… which stems from a debt of gratitude because of this liberating event.”

Most scholars involved in studying and trying to determine the actual route of the Exodus are Christian, he noted.

“Jewish scholars are more into the text and less into the archaeology,” he said. “Behind the text, what is the motivation? Who was writing this and for what purpose? Whose interest does it serve? One of the remarkable things about the Exodus story is how democratizing it is.

“Historically I don’t know what happened. But we have a piece of literature that claims an entire group of people were slaves, liberated and at Sinai. We all have the same humble origins; no one can claim themselves as from a higher family.”

The location of Mount Sinai

TO THIS day, any new theory proposed for the Exodus routes and location of Mount Sinai is purely based on speculation and analysis of where the sites mentioned in the Bible may have been; and for every theory presented, there is critique and counter theories.

However, despite the important symbolism it has, there is no Jewish tradition which cultivates the memory or location of Mount Sinai, noted Berman. There is no tradition of sanctity of the place, nor any special prayer for it.

“That is shocking if you consider what happened there, but it is also deliberate. To say that what happened in Mount Sinai is like a wedding – a one-time thing, and then we have to move onto the marriage. The marriage is what we are interested in. The relationship with God,” he said.

Still, a 1985 article in Biblical Archaeology Review by professors Avraham Perevolotsky of the Tel Aviv University Department of Environmental Studies, and Israel Finkelstein of the Department of Archaeology, notes that traditions locate “quite precisely” in southern Sinai a number of places associated with the Israelites’ Exodus history.

These places include: The burning bush, where Moses heard God’s call would have been, which they said is identified with a raspberry plant growing in the yard of St. Catherine’s Monastery; Mount Horeb, where Moses received the Ten Commandments according to the Book of Deuteronomy; and where, in the Book of Kings, the prophet Elijah found refuge – identified with Jebel Sufsafeh next to Jebel Musa; the hill where the Israelites worshiped the golden calf, with Nebi Haroun one kilometer west of St. Catherine’s Monastery; and, Mount Sinai with Jebel Musa, above St. Catherine’s Monastery.

“During the latter part of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries – in what we might call the pre-archaeological research age – two principal theories developed concerning the route of the Exodus journey through Sinai. These theories were developed by scholars who traveled in Sinai and based their conclusions on biblical textual evidence and on geographical evidence garnered during their journeys,” they summarized, notably not mentioning archaeological evidence.

The journeys took place on camelback, guided by Bedouin who knew the desert landscape well.

Finkelstein further wrote in his book The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, co-authored with American archaeologist Neil Asher Silberman, that along with other biblical stories, “Moses’ deliverance of the Children of Israel from bondage is but a brilliant product of the human imagination.”

In a 2021 article for the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology, archaeologist Christopher Eames notes that the “standard wisdom” holds that the route took the ancient Hebrews through the northern end of the Gulf of Suez, heading down into the Sinai Peninsula with Mount Sinai at the bottom of the peninsula.

“But,” he writes, “over the last several decades, there has been significant debate surrounding two other options: a “Bitter Lakes” option (crossing one of the shallow inland lakes much further north of the Gulf of Suez); or notably a Gulf of Aqaba crossing, on the far side of the Sinai Peninsula – leading into what is today Saudi Arabia.”

THE MAIN debate between the two routes, he says, is the identification of the location of Mount Sinai, which has given rise to some to consider the more distant location of the Gulf of Aqaba as the site of the mountain. His article goes on to compare the two theories based on analysis of biblical text, but again does not make any mention of any archaeological evidence.

The academic research on the biblical Exodus

Even former Trinity Evangelical Divinity School Professor James Hoffmeier, an American Old Testament scholar, archaeologist and Egyptologist, known for his body of research work on the Exodus, said in a 2020 lecture at Lanier Theological Library that he was “the first one to admit that we have no direct archaeological evidence concerning the Exodus.”

In his recorded lecture, Hoffmeier reviewed the background information from ancient Egypt, and focused on new geological and archaeological data from the work of the North Sinai Archaeological Project, which he directed. This work related to the possible geographical locations of sites mentioned in the Bible in Egypt, albeit based on the archaeological finds including brick-mud structures and fortresses.

Again, however, his lecture did not mention any archaeological evidence discovered of the 40-year sojourn through the desert. In his 1996 book Israel in Egypt, The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition, Hoffmeier contends that in the absence of direct archaeological or historical evidence of any part of the story, it is nonetheless possible to defend the possibility of such events, based on supporting evidence.

And yet, Dr. Racheli Shalomi Hen, a senior lecturer of comparative religion and archaeology at the Hebrew University, noted that the Exodus story is one of the most recognized founding myths, not only for Jews but also in Christianity and Islam. It is such a compelling narrative, that it has been adapted by many people who feel persecuted by another people. These include the people who fled Europe to what is now the United States escaping from church persecution, as well as African slaves who, after adopting Christianity, saw themselves as the Children of Israel under Pharaoh’s yoke.

“This is a huge story, and this is its power. Almost everyone can find themselves within this frame, to see themselves as a founder of a new era, a new nation after being persecuted and going through all this difficulty,” she said. “We only have the biblical text in reference to the Exodus story. We don’t have any evidence for that from any outside sources.”

But for a sizable number of Egyptologists, that does not dissuade them from their research on the story of the Exodus trail. Despite controversies about the story’s timetable, the possible routes taken and lack of evidence, Egyptologist Nicolas Grimal summed it up in his book A History of Ancient Egypt by saying that the lack of any surviving evidence of the event is “not in itself surprising, given that the Egyptians had no reason to attach any importance to the Hebrews.”

As a non-religious academic, nevertheless, Shalomi Hen said she does not believe the Exodus happened as is described in the Bible.

“We don’t relate to the Exodus narrative as history. We look at it as a cultural product that was created by someone who intimately knew Egypt, knew names, knew about Egyptian culture, their hopes and fears,” she said. “Whoever created this story knew exactly what they were doing, aiming at the Israelites and the Pharaoh. They wanted it to be a salvation story.

“But I will not argue with anyone who believes that everything is true because it is written in the Bible,” she added. “I do academic research and do not take anything for granted, especially not ancient texts which we have to look at with a critical eye. I do think there was something, some sort of events that sprouted and in a later time brought us this spectacular story, but what it was is impossible to say.”

Still, she said, to this day no outside evidence for such an Exodus has been found in any other sources, nor has any archaeological evidence – no bones, no garbage, no pottery or other utensils – have been found that could indicate desert wanderings of such a numerous group of people for such a long period of time.

If indeed as the Bible states, the Exodus involved 600,000 males and their families and animals crossing the desert – whether it be a northern route through the Negev or a southern route through the Sinai – some sort of archaeological remains would surely have been found in one of the countless archaeological excavations undertaken over the years in search of such evidence, she argues.

THE ACADEMIC world now points to the 13th or 12th century BCE, during the Ramesside period – conceivably during the reign of Rameses II – as a possible time for an Exodus or Exodus-like event of migration. According to Shalomi Hen, this Exodus is thought to have been by Semitic people who traveled west from Egypt (having originally lived in the western area of the Semitic region of Mesopotamia and the eastern Mediterranean coast, known in more modern times as the Levant) to return to their original territory. That is, the Canaanite area which today encompasses the regions of Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria and parts of Jordan.

There is also archaeological evidence of Egyptian cultural and religious contact and presence in the Levant – including in modern-day Israel. Archaeological excavations at a construction site in Tel Aviv by the Israel Antiquities Authority in 2015 even revealed a 5,000-year-old Egyptian brewery believed to be the northernmost Bronze Age Egyptian settlement.

Certainly, many ancient Egyptian records mention the presence of a Western Semitic population within Egypt coming as migrants looking for work or as prisoners of war, some of whom integrated themselves even into the higher echelons of Egyptian society through marriage and hard work.

The West Semitic Levant names of Tal and Shalom have been found on lists of servants from that time, said Shalomi Hen, with the prefix “amu,” a title indicating the servant position. The common Hebrew names Miriam and Pinchas have Egyptian origins, with Miriam a contraction of Meri-Amun – “beloved of the Egyptian god Amun” – added Berman.

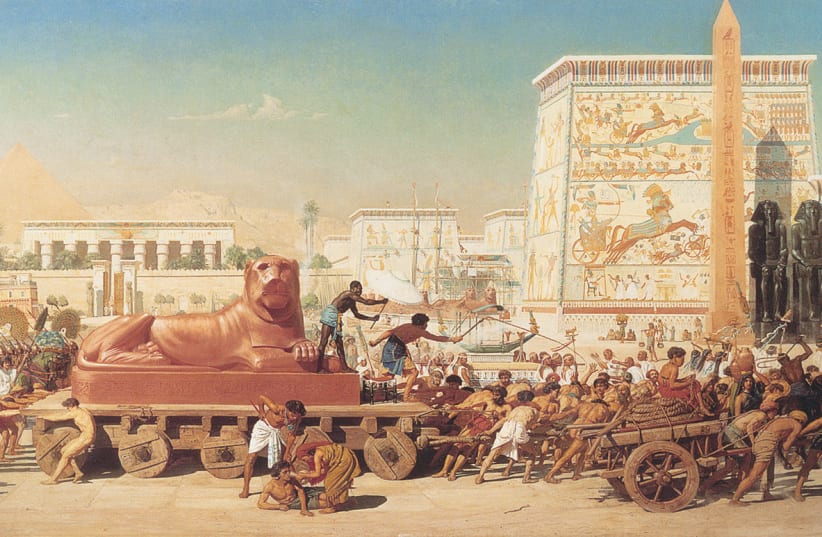

Indeed, Egyptian reliefs depict taskmasters looming over Semitic slaves, identifiable by their beards and facial features, making bricks as described in the Bible. Written sources also describe the brick-making process in similar terms.

“Canaan was a big place where different groups of people lived. The Israelites were (probably) a sub-group of Western Semitic Canaanite people. To the Egyptians, there was no difference; they all looked the same,” said Shalomi Hen.

THE FIRST mention of Israel as a people, rather than a people with a land, is on the Merneptah Stele, a victory inscription by the Pharaoh Merneptah, who reigned from 1213 to 1203 BCE, describing his military victories over Canaan, Ashkelon, Gezer and Yanoam in 1207 BCE. About Israel, he declared: “Israel is laid waste, bare of seed.”

There are ample records of Canaanites coming down into Egypt during times of famine, said Berman. While scholars can’t necessarily ascribe the ascent of Jacob to a specific text, the phenomena of famine and people flocking to Egypt, the powerful empire of the time, is well documented.

It is possible that at some time a Western Semitic population felt they were oppressed in some way, said Shalomi Hen.

“If we look at Exodus, it is clear that whoever wrote the text knew the Egyptian culture very well, and… the whole story was built… for two audiences. One, the People of Israel, and the other the Egyptians. The god of the Hebrews wants to make himself known and wants to make sure the Egyptians know that he is stronger.

“We are not speaking of monotheism here, not yet. We are speaking of the gods of Egypt, and [the Hebrew god] wants to show them he is stronger. There is an explicit expression of a real battle of gods, and the god of the Hebrews finds it very important to come first.”

The role of the pharaoh was to communicate between the people and the gods, and to maintain maat, a concept which encompassed the cosmic order, and anything that went wrong – such as a change in the climate or a poor harvest – was the king’s responsibility,” she said.

“If you look at the story of the plagues, you understand that the biblical author knew very well this role of the Egyptian king and aimed at that concept to show that the pharaoh had failed and could not deliver,” she said. “Like in a play, we do have the setting for the story of Exodus.”

In his writing, Berman maintains that to really understand the Bible’s intent, one must understand it within its Ancient Near Eastern context, and modern definitions of truth or fact should not be imposed upon it, as such concepts did not exist in the ancient world.

“I am convinced there is a core here that must be true. I don’t see how the core could exist with Israelites not being in Egypt and having this experience which they took to be liberation,” he said, adding, “and any embellishments in the recounting of the story does not make it simply a myth.”

The text is intended for the reader to come in submission in order to teach a lesson, he said. The need to know what is factual and what is not is a modern-day “hang up,” he said, where people feel if it is not 100 percent factual, then it is fake. This, he said, is a new way of reading.

“I wrote a whole book about how the Torah revolutionized ancient thought. Taking from Kings and temples, and giving a new standing to the common people,” said Berman. “The amazing thing is that it is hard to see who the big beneficiary of this (would be)...landholders, priests? None of the above. Not even the people. What the Torah says is this is all fragile, and if you don’t stand up to the contract, it will all be taken away from you.”

A concept, perhaps, to indeed be contemplated as Jews all over the world, and especially in Israel, sit down to the Seder meal this year.