Given that Yiddish was illegal in the early years of the state, it is remarkable how many Yiddish-focused organizations and institutions exist in Israel, or that there is a National Authority for Yiddish.

Founding prime minister David Ben Gurion, who outlawed this language, which was most common among European Jews, could speak an excellent Yiddish himself, and did so when he needed to schnor (ask, beg) money from affluent Jews in the diaspora, but in his view, if Hebrew was to be the unifying language in the newly reclaimed homeland of the Jewish people, Yiddish had to be eliminated.

Obviously, it was a failed attempt on his part. In ultra-Orthodox circles, many people opted not to discuss everyday matters in the holy tongue and preferred to speak Yiddish. Holocaust survivors learned to speak Hebrew to their children, but spoke Yiddish amongst themselves and supported Yiddish cultural projects.

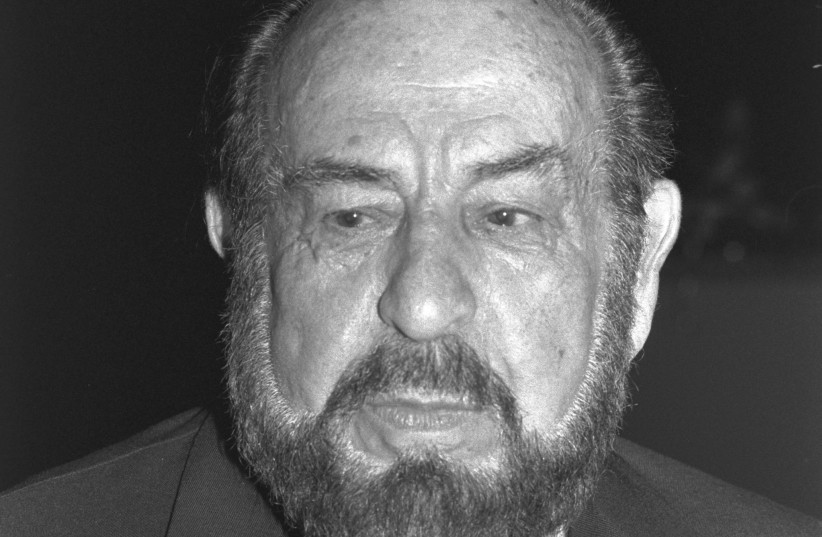

Visiting Yiddish Theater productions were permitted, but it took a while for a local Yiddish Theater to gain a hold. Yiddishpiel, the Yiddish Theater, with numerous productions to its credit, was founded in 1987 by Shmuel Atzmon-Wircer, in a bid to revive what had for so long been the common language of European Jews. Long before the advent of Yiddishpuel, Atzmon-Wircer, who will celebrate his 93rd birthday on June 29, appeared in a Yiddish comedy team The Three Shmuliks with Shmuel Rodensky and Shmuel Segal. All three were regular Habimah actors with a great love for Yiddish. Rodensky was born in Russia, and Segal and Atzmon-Wircer in Poland. This December, Habimah will probably mark the 120th anniversary of Rodensky’s birth.

The First World War and its aftermath created turmoil not only in the material world of Eastern European Jewry, but with its changing boundaries; it also left a deep impression on its spiritual world and on the developing Yiddish modern culture. Out of the ruins of the war arose the avant-garde of Yiddish literature and art.

Last week the Rena Costa Center for Yiddish Studies at the Department for the Literature of the Jewish People at Bar-Ilan University, in cooperation with the Center of Yiddish Culture at the Department of Hebrew Literature at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, and the Program of Yiddish Language, Literature and Culture of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, marked the 100th anniversary of Khalyastre (Yiddish: gang) by hosting an international conference at Bar-Ilan focusing on avant-garde in Yiddish culture. Khalyastre was a Yiddish avant-garde literary group with its own publication, established in Warsaw, in 1922.

Avant-garde

Yiddish avant-garde activity was characterized by sporadic gatherings of authors and artists in different European cities, such as Kyiv, Moscow, Lodz, Warsaw and even Berlin. They produced a variety of other journals, among them Eygns, Shtrom, Yung Yidish, Ringen, Milgroym and Albatros, but the best known was Khalyastre. Conference panels at BIU focused on avant-garde art, theater, poetry and linguistics, and included the participation of scholars from all over Israel, Heinrich Heine University, Selma Stern Center for Jewish Studies Berlin-Brandenburg and European University Viadrina (Germany), as well as Columbia University, Tulane University and Indiana University.

In his keynote lecture, Yiddish scholar Prof. David Roskies of the Jewish Theological Seminary traced what he called the broken timeline – the years from 1938-1945, in which the achievements of Yiddish modernism were completely erased. The Jewish world, he said, had to bury its past, due to the trauma it suffered at the hands of Stalin and Hitler. Roskies focused on how this lost chapter in history was expressed simultaneously, yet differently, in three countries: the former Soviet Union, Poland and the United States, and highlighted the resurgence of interest in Yiddish culture in the 1970s.

“The avant-garde brought about a revolution in Yiddish culture by bringing new ideas, new content, new insights, and new methods and shapes in literature, art, language and theater,” said one of the conference organizers, Prof. Nati Cohen, Director of BIU’s Rena Costa Center for Yiddish Studies, who initiated the gathering. “All of the realist and sentimental literature and art that existed until then became passé and a new, expressionist era in Yiddish culture was born. Rather than looking at what was happening on the outside, authors and artists began to express current events introspectively.”

With a new kind of vocabulary never before used, Yiddish avant-garde shook up the established literary world and was often misunderstood by readers – even generating anger among critics. For example, in his poem “Di Kupe” (The Pile), the poet Peretz Markish shocked readers when he vividly described a heap of victims of a pogrom in Ukraine and critics of the time looked upon this writing as something sick, according to Cohen.

In another poem, Uri Zvi Greenberg changed the image of Jesus, who was no longer the pure and perfect messiah but a brother who suffers for being Jewish. “The code for this new literary writing was not beauty but horror. In their 1922 manifesto, the Khalyastre gang of poets wrote that literature was no longer pleasant and euphoric, but reflected the cries of the shocking pain of a mountain that falls into an abyss,” explained Cohen.

Three decades after the appearance of the avant-garde gatherings and journals, some of the authors were among those murdered in the bloodbath that destroyed Yiddish literature in the Soviet Union, in August 1952.

Though it was a relatively small and temporary group in the history of Yiddish culture that only lasted for approximately two years, Khalyastre left its stamp for many decades, according to Cohen. Today, Master’s and doctoral students still write their theses about this group and its influence, discover new information and present new analysis. “This group symbolizes how much Yiddish culture was a kind of dynamic civilization in all aspects of the artistic world

■ THERE ARE more than 500 alumni who participated in the One Year Program of the Hebrew University Rothberg School for Overseas Students during the 1971-72 academic year. One of them is Terry Cohen Hendin, who with her husband who is also an alumnus of the program, has been in Israel for 47 years. Many of their classmates include veterans, as well as some newer immigrants. A small core group of those who live in Israel keep in touch and until COVID-19, would enjoy small intimate gatherings in each other’s homes, often scheduled around the visits of other alumni who were in Israel to renew contacts with family and friends.

COVID-19 got in the way of plans for a 50th anniversary reunion, but some of the Israel-based alumni are gearing up for a relatively small reunion event on July 3 at Kehillat Ya’ar Ramot. Hendin and fellow organizers want to reach out to other alumni with whom they are not personally in touch, in the hope that they will want to join the reunion. Anyone who qualifies and is interested should email Terry Hendin at HU50Reunion@gmail.com.

■ VERA WEIZMANN, one of the co-founders of the Women’s International Zionist Organization (WIZO) and the wife of Israel’s first president Chaim Weizmann, told her story in a book called The Impossible Takes Longer. The title could also apply to the evolution of women’s rights in Israel in the quest for equal opportunity, equal pay for equal work, and equal respect for achievement.

Now, in a long-overdue step, WIZO, in conjunction with the Education Ministry, where both the Minister and the Director General are women, has succeeded (for as long as the government remains in office) in introducing to school curricula the contribution of women to the creation and development of the state of Israel. Women have done some amazing things in this country and deserve to be acknowledged. Golda Meir is always held out as an example, but there were so many other great women, among them Mania Shochat, Hannah Senesh, Rachel Yanait Ben Zvi, Rebecca Sieff, Ada Kagan, Sarah Herzog, Miriam Ben Porat, Shoshana Damari, Yaffa Yarkoni, Ada Yonath, Raya Jaglom, Karnit Flug, and many others too numerous to mention.

But it’s about time that women received their due place in history as founders of kibbutzim and moshavim, educators, lawyers, judges, journalists, scientists, physicians, industrialists, politicians, social workers, bankers, economists, fashion designers, architects, filmmakers, athletes and more.

Let’s not forget that Israel’s first Olympic medal, 30 years ago, was won by a woman, judoka Yael Arad. Over the past century, there has been a lot of positive change, but one of the biggest bugbears is still the struggle to receive equal pay for equal work. Hopefully, that too will eventually change.

■ NOT EVERYTHING is becoming unaffordable due to rising prices. In the fashion industry, prices are actually being reduced – maybe because there are fewer sales as people spend more on food and other necessary consumer products. Summer has only just arrived, and Castro, which is one of Israel’s leading brands, has already introduced its end of season summer sale, with 50% discounts on many of the items in its summer 2022 collection, bearing in mind that winter is still a long way off and that global warming indicates that summers will be longer and winters shorter in the future. Castro is not alone in reducing prices. Many other fashion outlets are doing the same.