‘War breeds revolutions,” the historian Paul Johnson once observed. “And breeding revolutions is a very old form of warfare.” Amnesty International has been in the news recently for a biased report labeling Israel as an “apartheid state.”

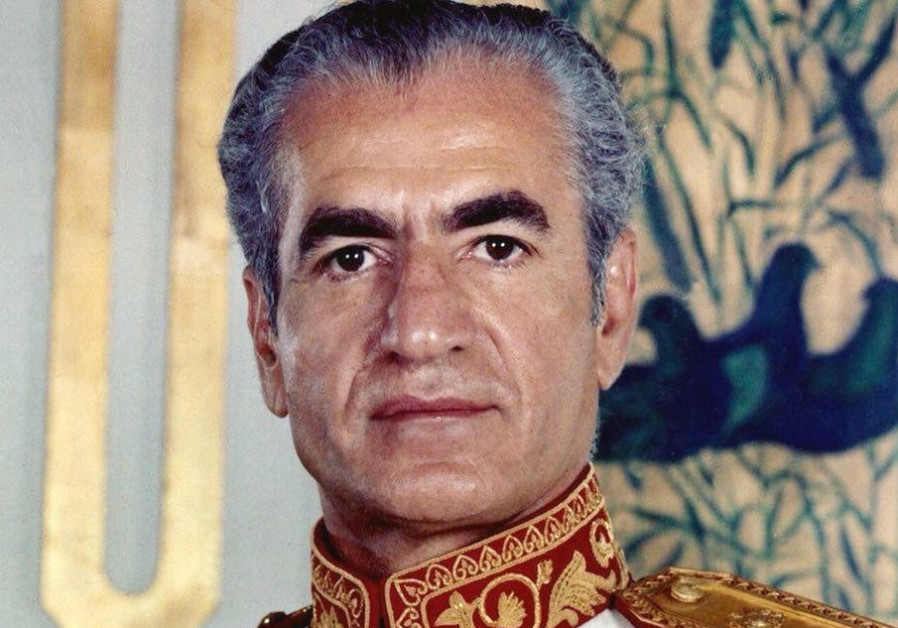

Yet, it is far from the only time that the NGO has engaged in shoddy reporting with destructive results. Amnesty, it turns out, played an important role in events leading up to the overthrow of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran.

The details, while seldom noted by press and policymakers, can be found in Andrew Scott Cooper’s 2018 book The Fall of Heaven: The Pahlavis and the Final Days of Imperial Iran.

Cooper, a historian and former researcher for Human Rights Watch, found that the “historical record” of the shah’s human rights abuses “was manipulated by Ayatollah [Ruhollah Khomeini] and his partisans to criminalize the shah and justify their own excesses and abuses.” Amnesty, if unwittingly, aided these efforts.

The shah ascended to the throne in 1941, following his father’s abdication. He would rule for 38 tumultuous years, attempting to modernize his country. He largely succeeded.

Yet as Cooper notes “the controversy and confusion that surrounded the shah’s human rights record overshadowed his many real accomplishments in the fields of women’s rights, literacy, health care, education and modernization.”

The shah’s hopes to bring Iran into the 20th century spurred opposition from some religious clerics and others. The growing expectations of a rising middle class and credible allegations of corruption led to an increasingly rocky decade in the 1970s. A cancer diagnosis also led to the shah attempting to speed up reforms so his son could inherit a more stable and prosperous Iran.

The shah’s opponents – an odd coalition of sorts that ran the gamut from moderate reformers to communists to Islamists – sensed an opportunity. And a key part of their strategy was to discredit the shah.Human rights abuses did, of course, occur in imperial Iran, where political prisoners were jailed and tortured. But the scope, recent studies suggest, was vastly exaggerated.

As Cooper notes, when the Islamic Republic announced plans to identify and memorialize the victims of the Pahlavi government, lead researcher Emad al-din Baghi “was shocked to discover that he could not match the victims’ names to the official numbers: instead of 100,000 deaths Baghi could confirm only 3,164.”

Yet, “even that number was inflated because it included all 2,781 fatalities from the 1978-79 revolution.” Accordingly, “the actual death toll was lowered to 383, of whom 197 were guerrilla fighters and terrorists killed in skirmishes with the security forces.”

This, Cooper recounts, meant that “183 political prisoners and dissidents were executed, committed suicide in detention, or died under torture. The number of political prisoners was also sharply reduced, from 100,000 to about 3,200.”

Importantly, these figures also match the estimates that the shah provided to the International Committee of the Red Cross in the years preceding his 1979 overthrow. Cooper even concludes that “Baghi’s estimates might still be too high,” noting that the shah was blamed for numerous deaths that can now be laid at the feet of Khomeini’s forces.

The historian was also assured by current and former staffers of the Center for Documentation on the Revolution in Tehran that the reduced figures are correct.

This, of course, doesn’t diminish the very real abuses that occurred while the shah was in power. But it must be noted that these figures pale in comparison to the bloodletting perpetrated by the Islamist dictatorship which came in the shah’s wake.

As Cooper points out, “During Khomeini’s decade in power, from 1979 to 1989, an estimated 12,000 monarchists, liberals, leftists, homosexuals, and women were executed and thousands more tortured.” In one week alone in July 1988, the mullahs murdered an estimated 3,000 men and women.

HOW, THEN, did the image of the shah as a bloodthirsty dictator become a reported “fact”? Several organizations, Amnesty foremost among them, portrayed the shah as precisely that.

In 1976, Amnesty International filed a report asserting that the “execution of political prisoners” was widespread. Amnesty, Cooper noted, “repeated claims made by the Iranian opposition groups that between 25,000 and 100,000 people were in jail on trumped-up political charges.”

Subsequently, the International Commission of Jurists described human rights violations as “unprecedented” – this, Cooper points out, at a time when Pol Pot’s dictatorship ruled Cambodia and Idi Amin ruled Uganda with an iron fist.Amnesty’s report was influential.

Several members of the US Congress would cite it when opposing military aid to the shah in his final years in power. Prominent journalists like Mary McCory would treat it as gospel, questioning the need for American support and calling the shah an arms “junkie who mainlines on anything that flies, shoots or is armor-clad.”

The New York Times, among others, would treat Amnesty’s claims as “established” fact – and the Times’s reporting would be cited, archives now reveal, by the CIA.

Khomeini certainly knew how to play the press. His aides instructed him to tell Western reporters that “we want democracy and rights for all,” noting “this is what the Americans like to hear.”

Jonathan Randal, a Washington Post correspondent based in Beirut, was encouraged by Khomeini allies to write stories on the shah’s human rights abuses. The journalist, Cooper notes, even agreed to drive to a bazaar and “collect a suitcase that turned out to be full of cash and bring it out of the country.” Randal had been “manipulated” by “anti-shah propagandists.” The Carter administration felt the pressure.

Senator “Scoop” Jackson felt that the administration’s subsequent criticisms of the shah “conveyed to the Iranian public that we were going to dump him.”

Presciently, Jackson warned that with Khomeini at the helm, Iran “would become a base of operations of the PLO and a significant source of strength for radical Arab regimes. This… shift means increased danger for Israel” and a “shift in the balance of power of historic proportions.”

The consequences of that shift are still being felt today, with a regime whose systemic human rights abuses vastly exceed even the most fervent imaginations of the shah’s critics four decades ago.

The writer is a senior research analyst for CAMERA, the Boston-based Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting and Analysis.