KYIV, Ukraine — Islamic State’s leader, killed by American commandos Thursday, was a largely reclusive figure with almost no public presence, despite heading the world’s most notorious terror group.

To the group’s adherents, he was known as Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi, a nom de guerre he adopted when he became Islamic State’s self-styled caliph, one week after his predecessor, Abu-Bakr al-Baghdadi, was killed in a raid in late 2019.

Unlike Baghdadi, Qurayshi (his last name was meant to link him to the tribe of the Prophet Muhammad) presided over a much diminished force, a shadow of the group that at its height in 2015 presided over a swath of territory the size of Britain, a so-called caliphate that encompassed a full third of Iraq and Syria each.

By the time Qurayshi came to power, that was long gone: In 2017, a US-led coalition, working in concert with Kurdish militia members, overran the tiny Syrian hamlet of Baghouz, the last of Islamic State’s caliphate. Those of the group’s cadres who weren’t killed or captured moved to remote rural and desert areas of Iraq and Syria, where they have since waged a mostly low-level insurgency, including hit-and-run attacks, assassinations and drive-by shootings.

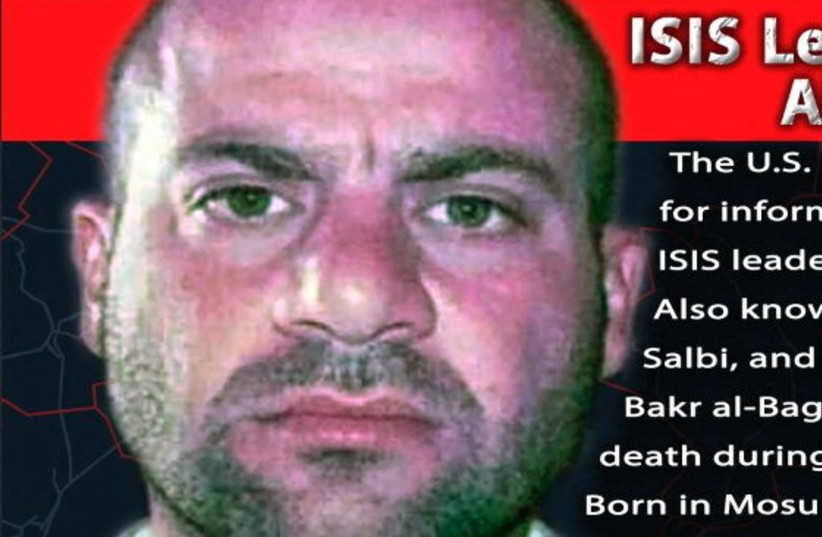

Qurayshi’s profile reflected the group’s shadow existence: Where his predecessor’s face was known the world over and had appeared in a widely circulated video announcing the caliphate, not to mention frequent appearances in photos and audio speeches, Qurayshi was never seen or heard and issued no statements.

“Abu Ibrahim wasn’t much more than a name. With Baghdadi, ISIS had troves of history, biographical information and speeches to understand him by,” said Rita Katz, executive director of SITE Intelligence Group, using the acronym for Islamic State. “But with Abu Ibrahim, they had no speeches, no pictures, no biography.

“ISIS didn’t even publish his real name — only his nom de guerre,” she continued. “The only reason we know as much as we do about him is from intelligence reports and investigations — many of which remain hazy.”

Even after his death, there remains conflicting information about his identity. His name, according to various intelligence agencies, was Amir Muhammad Sa’id Abdal-Rahman Mawla. One of his aliases was Hajji Abdallah Qardash. Abdul Amir Muhammad Sa’id Salbi was another.

He was born in 1976, either in the northern Iraqi town of Telefar, a longtime bastion of Islamic State support and home to some of its most vicious enforcers; or in Mosul, the Iraqi city that became Islamic State’s capital in 2014. He was said to have a degree in Shariah, or Islamic law, from Mosul University.

What the various biographies do agree on is that he was a veteran insurgent operator, one who had joined Islamic State’s progenitor, al-Qaeda in Iraq, and for a time was even detained in Camp Bucca, the notorious American prison in southern Iraq, where he met al-Baghdadi. He rose through the ranks to assume the role of the group’s deputy leader, the US State Department said in its 2020 “Rewards for Justice” call for Qurayshi, assigning a reward of $10 million for a figure they said “helped drive and justify the abduction, slaughter and trafficking of the Yazidi religious minority in northwest Iraq and also led some of the group’s global terrorist operations.”

When Islamic State marched through Iraq in 2014, it took over the Yazidi homeland in the Sinjar region of northern Iraq. The group’s fighters launched a vicious genocide campaign, murdering 3,000 men and boys — shooting them execution-style in the back of the head and pushing them off cliffs — and kidnapped thousands of women and girls to use as slaves, sexual and otherwise, in their caliphate. Years later, many Yazidi remain missing; those who did return are often ostracized by their families.

That there was no public element to Qurayshi’s tenure , Katz said, was a function of security. But it also mattered little to the group’s various branches in West Africa and elsewhere.

“The community at large pledged to the new leader right after he was announced. Nobody cared that he didn’t even deliver a message,” she said.

Indeed, the first concrete word concerning Qurayshi since his appointment more than two years ago was his death on Thursday.

The operation to kill him unfolded just before 1 a.m., when helicopters hovered over a remote corner of Atmeh, a border town in the northwestern province of Idlib that is home to tens of thousands of internally displaced Syrians. One helicopter suffered a mechanical failure in the initial phase of the operation, Pentagon spokesman John Kirby said Thursday, adding that it was forced to land in an area away from the target and was later destroyed by American forces.

Residents interviewed by local news outlets said the helicopters hovered for a time over a gray, cinderblock two-story building with a basement level. One of them landed and special forces operatives disembarked and surrounded the building.

Several videos — which the Los Angeles Times could not verify — show what happened next: In one clip, the sounds of heavy machine gunfire rips through the night, while muzzle flashes twinkling somewhere above; another shows the building’s entrance ablaze, and a voice on a loudspeaker in Arabic telling the building’s occupants that the area was surrounded, that they should surrender, and that if they did not want to they should let the children come out.

The standoff soon gave way to an all-out battle, with one of Qurayshi’s “lieutenants” and his wife engaging US forces and subsequently being killed. Qurayshi, meanwhile, detonated his explosive vest, killing three other people with him, Kirby said. Two hours later, a little after 3 a.m., the helicopters departed.

Video taken by a reporter with Al-Akhbar Al-Aan, a news channel based in the United Arab Emirates, purported to show the aftermath of the raid. The clip shows a scene of destruction, with cinderblocks spilling over the side of the building where ordnance had struck; rubble and detritus covering the floor along with a big smear of blood. Rescue workers with the Syrian Civil Defense, a group of first responders known as the White Helmets working in opposition-controlled areas, reported that at least 13 people were killed during the raid, including six children and four women. They also provided medical assistance to a young girl who lived in the building and whose family was killed in the attack, and to a man who approached the area and was injured in the clashes.

“Knowing that this terrorist had chosen to surround himself with families, including children, we made a choice to pursue a Special Forces raid at a much greater risk to our own people rather than targeting him with an airstrike,” President Joe Biden said. “We made this choice to minimize civilian casualties.”

Qurayshi’s death echoed that of Baghdadi, who blew himself up when US forces raided his hideout in Barisha, another tiny village in Idlib near the Turkish border, some 10 miles southwest of Atmeh.

Idlib, a verdant province once famous for its olive groves, has since become the last bastion of those opposed to the government of Syrian President Bashar Assad. The province is controlled by Hayat Tahrir Sham, or HTS, a jihadist umbrella group that includes a former affiliate of al-Qaeda in Syria but that considers Islamic State its avowed enemy. Observers noted that the strike area was only a few hundred yards from an HTS checkpoint and that the group’s fighters set up a security cordon preventing people from entering the area.

Qurayshi had been masquerading as a Syrian man from the city of Aleppo, said the owner of the building in an interview with Sham, a Syrian pro-opposition news channel. He said Qurayshi rented the apartment 11 months ago, along with another person who rented the floor above.

Biden administration officials hailed the raid as a success. But it comes at a time when Islamic State appears on the cusp of a resurgence. Last month, it launched a complex operation to release cadres held in prisons run by US-backed Kurdish militiaman. That operation was thwarted by Kurdish fighters and US forces using both drones and Bradley armored vehicles, but it took 10 days. Experts also point to the deaths of other leaders of jihadi groups in the past and the little effect they had on Islamic State.

“History has repeatedly shown that killing jihadi leaders — even the most prominent and important among them — won’t kill the movement,” Katz said. She mentioned al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, who was killed by US forces in 2011, and al-Qaeda in Iraq leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who was killed in 2006.

“Just look at Osama bin Laden and Zarqawi, the two most charismatic and movement-inspiring figures of the global jihad,” she said “If their deaths didn’t blunt the movement, why should we expect the death of a faceless, voiceless figure like Abu Ibrahim to?”