Mark Twain was one of the great writers of American literature, and surely one of the funniest. He was also a famously obscene conversationalist. Helen Keller reports being shocked by how many vulgarities Twain used in everyday speech. Twain’s wife, having devised a strategy to cure her husband of this tendency, one day surprised him by letting loose a stream of curses herself to show him how it sounded.

“Honey,” said Twain, “you have the words, but you ain’t got the music.”

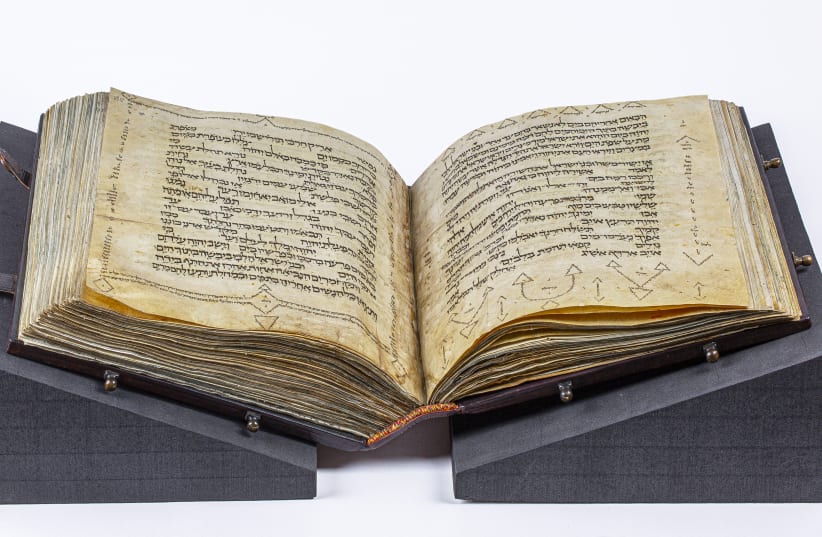

In Jewish tradition there are words one is not supposed to say. In this week’s Torah portion, we are told the blasphemer should be put to death (Leviticus 24:16). That words could be fatal was taken very seriously.

In the later book of Job, when Job’s wife gives him the advise to curse God and die, she actually says “bless” God, because to say the opposite would skirt too close to actual blasphemy. (This is lashon sagi nahor – the language of sufficient light, which is how one refers to the blind. In other words, to avoid the harshness of certain words, you say the opposite, but the meaning is understood.)

It seems from Job’s wife’s expression that she believes blaspheming God will lead naturally to death; this is a sort of theological euthanasia, the way to end suffering is simply blaspheme and it will all be over.

ON CLOSER inspection, the tale of Judaism and blasphemy is more complicated than it may appear. We must pay attention not only to the word, but the subsequent music.

In the Talmud, the rabbis posit that one who hears blasphemy should tear his garment. Then Rabbi Hiyya explains the true state of things: “One who hears a mention of God’s name in a blasphemous context nowadays is not obligated to make a tear, as if you do not say so, the entire garment will be full of tears (Sanhedrin 60a). In other words, blasphemy had become so common that marking it was impossible. Far from a rare breach that would incur death, it was rampant.

Even when careful to avoid blasphemy, the rabbis sidestepped with great skill. Making a play on the verse “Who is like You among the gods?” (elim) the school of Rabbi Yishmael taught, “Who is like you among the mute? (illemim) (Gittin 56b).” After all, God has a disconcerting habit of not joining in when the Divine voice would be deeply appreciated. Still, labeling God as dumb is pretty daring, and could certainly be seen by some as blasphemy.

Yet even this is building on an earlier tradition. Abraham already questions God’s justice when told Sodom is to be destroyed: “Shall the judge of all the earth not do justice?” (Genesis 18:25). Blasphemy may have been interdicted, but the impulse to hurl indictments toward heaven found ways of expressing itself.

All of this reminds us that listening to objectionable speech and learning how to deal with it is part of the natural linguistic immune system. In the same way that letting kids play in dirty fields builds up their resistance, allowing words to range freely gives us a way to cope with words whose import we object to or even despise.

This is continuous with the wisdom that objects to banning books. It is good for the young to react to powerful ideas. They should grapple with them and grow out of them. We did.

And one must hear things to understand why they might be believed and how they can be argued against. Ruling ideas and expressions out of court does not make them disappear, it just labels them as explosively powerful. We need to relearn the Talmudic practice of preserving the rejected as well as the accepted opinions.

After all, the central declaration of the prayer service is not to speak, but to listen, Israel. ■

The writer is Max Webb Senior Rabbi of Sinai Temple in Los Angeles. On Twitter: @rabbiwolpe