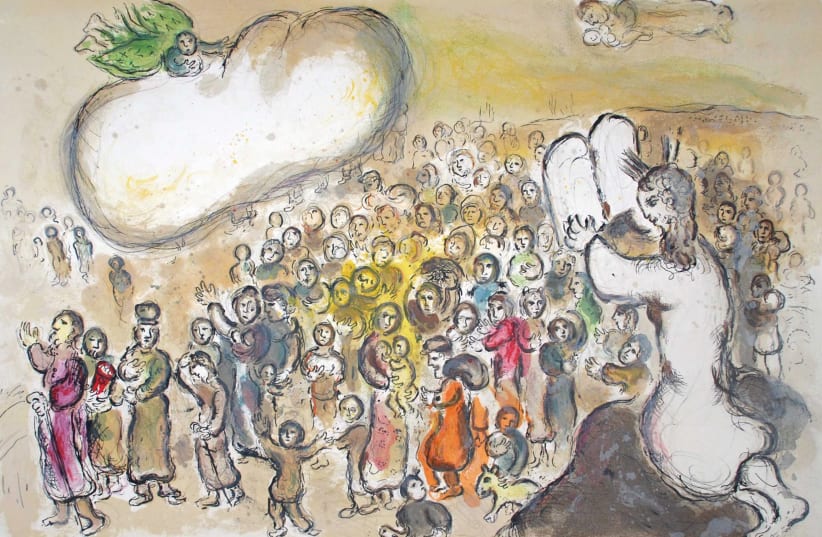

One explanation is that it was pure rage. Once he saw the Israelites dancing about an idol, Moses could no longer contain himself.

But this seems inadequate. Why should his reaction to the perfidy of the people be to destroy the work of God, the most valuable single item in the history of the world? Was he that incapable of self-control? Better to have marched back up the mountain to deposit the tablets somewhere safe.

Arnold Ehrlich, author of Mikra Kipshuto, has a provocative and interesting answer. He notes that the Rabbis relate that God said to Moses: “Yishar kohacha that you broke them!” (Shabbat 87a). God apparently approved of Moses’s action. This signals that more than anger was at stake.

Ehrlich believes that Moses saw the calf and thought: If the Israelites worship this calf, which they created with their own hands, what will they do when they see the tablets carved by God? Surely, they will turn these tablets, which are so much more precious than the calf, into an idol! If I don’t destroy the tablets, they will commit the ultimate desecration.

By smashing the tablets, Moses was making a declaration to all of Israel: Even the handiwork of God, which you might think of as inviolable, is nonetheless just another thing. It is not a God – it is a physical artifact. I am destroying it to return you to the greater truth, which is that you were not delivered from Egypt by a thing, but by an intangible, unfathomable God, no more embodied in the tablets than in the calf.

Idolatry is a persistent temptation to human beings. Modern observers are often surprised when they see or read that digging up an ancient Israelite site, there are idols, especially fertility idols, in abundance. But we should not be surprised; the prophets are always yelling at the Israelites about worshiping idols, and one doesn’t yell at people repeatedly to stop doing something that they never do. Idolatry was rife in Israel, and combating it was a long, difficult project.

To take an object as in some sense Divine is to limit the reality of God, to make God small. Anything limited that evokes absolute devotion is idolatry. For the only absolute is God. An idol suggests that somehow things can be measured in human terms, that our capacities are sufficient to comprehend the transcendent. Idolatry is not only about making God small, but also about making human beings too big.

Perhaps the people did not conceive of the idol itself as a god (for after all, as Ramban argues, the golden calf was more a substitute for Moses than God – it was when Moses disappeared that the people built it). But, as Solomon Schechter wrote, establishing an intermediary between God and human beings is tantamount to setting up another God, which is always a cause of sin.

The Israelites were not ready for the direct, unmediated relationship to God. They wanted something they could touch or see, to prove the reality of what they could not see. But Judaism refashioned ritual objects from good luck charms or conduits to God into reminders and symbols of our history and connection to God. We took the physical and stripped it of its ultimate power in the minds of human beings, for ultimacy belongs only to God.

The golden calf was a turning point in history not only for the sin but for Moses’s reaction. Moses smashed the tablets forever and always not to punish but to elevate. The fragments remind us of the fate of all physical things, but the message reminds us of the eternity of the Creator of all.

(For those who wish to study the meaning of idolatry more deeply, Kenneth Seeskin wrote a wonderful short book, No Other Gods, and Moshe Halbertal with Avishai Margalit a more comprehensive philosophical guide, Idolatry.) ■

The writer is the Max Webb Senior Rabbi of Sinai Temple, Los Angeles. Twitter: @rabbiwolpe.