In the fall of 1977, I was gearing up for my bar mitzvah, spending long hours working with my tutor, Rabbi Halon, who saw something in me and gave me great attention. I took to memorizing the Torah and haftarah portions I would recite in early January.

While I did my job well enough, in fairness, in addition to two afternoons a week and Sunday mornings at Hebrew school, I did what I needed to do. But I found myself challenged to make a commitment to this additional and sometimes burdensome work that was more a distraction than something I embraced.

My memorization of parashat Bo (Exodus 10:1-13:16) was passable, maybe even very good minus some obvious glitches about which I still laugh today.

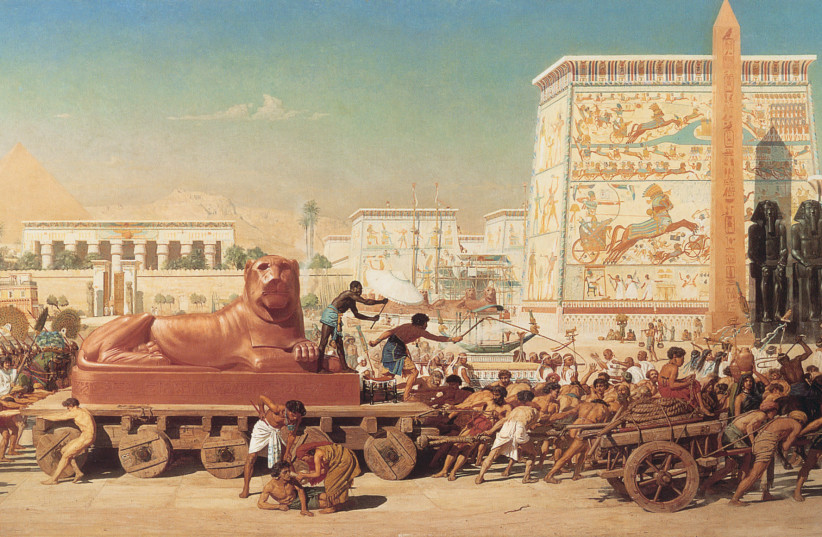

During my studying, I was struck with the narrative of the last three plagues God brought upon Egypt, and the redemption of the Jewish people from slavery thousands of years earlier.

Thousands of miles and another world away, Jews in the Soviet Union were enduring their own slavery. As a not quite yet 13-year-old, while I knew well of our slavery and liberation from Egypt, I was unaware of what was happening to millions of Soviet Jews. In that parallel universe, Jews were in the midst of an awakening that included studying Hebrew, embracing Jewish culture and religion, and preteens my age also secretly preparing for their own bar and bat mitzvahs. I was aware of none of it, or the risks they took doing so.

The differences between my bar mitzvah preparation and those actively affirming their place as part of the Jewish people and all facets of that, could not have been starker.

My preparation involved a pilgrimage to Barneys to buy the (required, brown) bar mitzvah three-piece suit. I had the luxury of finding my Hebrew and religious studies inconvenient, even annoying.

On the other side of the world, the inconvenience and annoyance were a result of the secretive nature of their studies and the discriminatory consequences, which could be grave, including being fired from one’s job, expelled from school and imprisoned.

I met my friend Ephraim Kholmyansky in Moscow in 1987. While I was on the verge of becoming a bar mitzvah a decade earlier, so was he. As he wrote in his book The Voice of Silence, “From the fall of 1977 on, Hebrew lessons became the highlight of my week: three or four hours once a week, with only a short break for tea.”

Not only could I have not been much more distant from that passion to study Hebrew, I surely never would have considered it a highlight of my week.

I also did not know anything about how he and many others who studied Hebrew underground put themselves at risk for this.

I did not know that Soviet Jews were largely persecuted, prevented from practicing our religion, learning our culture or studying, much less teaching, Hebrew. I did not know that Jews who openly identified as wanting to leave the USSR, much less applying for that opportunity, became stuck in a web of state-sponsored harassment.

My religious life and bar mitzvah preparation were things I took for granted, even a bit of an obligatory annoyance.

I did not understand the cultural and religious genocide to which the Jews of the Soviet Union were subject, or the heroism involved just in standing up to claim their heritage.

But I did understand that the persecution and enslavement of the Jewish people in Egypt was part of our DNA.

FOUR YEARS later, in the months leading up to my brother’s bar mitzvah, my mother read a Hadassah Magazine article at the kitchen table one evening about the plight of Soviet Jews and, among other things, the practice of young Jewish boys and girls to twin their bar and bat mitzvahs with peers in the USSR.

I understood the idea of our people being enslaved, and that while God delivered us from Egypt, we were being enslaved again.

The same way I had chosen to take my own Hebrew and religious studies with limited seriousness, despite Rabbi Halon seeing promise in me, I made a proactive determination then and there to do whatever I could to be part of liberating our enslaved people. I realized that because I was free, I had the choice, not just to take my studies less than seriously, but also to do something for others still enslaved.

The lesson of my bar mitzvah studies years earlier had stayed with me. On the day of the Exodus, in my parasha, God commanded us to “Remember this day, when you went out of Egypt, out of the house of bondage, for with a mighty hand the Lord took you out of here.” I remembered, and ran to embrace this charge that I felt I was being called to carry out, imbued with the injunction from my bar mitzvah.

I undertook to do everything I could to free our people. I adopted a Jewish refusenik family of my own.

As I learned about the plight of Soviet Jewry, while not denying God’s presence, I didn’t see Him performing miracles and plagues, the three last of which were in my parasha and pushed Pharaoh over the top: locusts, darkness, and death of the firstborn. So, if God was not performing dramatic miracles and plagues Himself, that gave me an opportunity, maybe even the obligation, to jump in to do my part. Maybe God’s intended paradigm was different this time: “I saved you from slavery the first time. This time, let’s see what you’ve got.” Maybe He was offering me and others some kind of Divine partnership.

Within a year I was writing my college admission essays, basically giving fair warning that wherever I was going to end up, my college would become my battlefield in the liberation of Soviet Jews. I didn’t know what that meant, but then again neither did Moses each time God sent him to Pharaoh.

In my first year in college, I got Emory to adopt my adopted refusenik family, which made my platform to advocate on its behalf even bigger. By the end of my second year, a plan was hatched, and I was off to my first trip to Moscow to rescue my adopted family.

By 1987, when I met Kholmyansky, who had already done time in Soviet prison for teaching Hebrew, my adoptive family was free. But there was still more to do. My parasha taught me that.

I don’t know that there’s a biblical model for the widespread, grassroots human action that helped to free millions of Jews from Egypt. But, albeit coming to the movement late, I felt that God was telling me to take action. If I had had access to the Kremlin the way Moses did to Pharaoh, I suspect I’d have gone there, too. Instead, along with many other activists, I played a small role in helping to liberate millions of Jews from the USSR.

That’s the lesson I learned from my bar mitzvah, and it remains with me over four decades later. ■