Ruth Schreiber (née Merel) is a multi-faceted artist who lives in Jerusalem, but whose family memories root her in England and before that in Germany. These memories were awakened not only by the usual route of family memorabilia, but also by a local, non-Jewish, German amateur historian, Rainer Zeh, from Sassanfahrt – the home of the Merel family in the 1930s – who along with a growing number of other Germans, had been curious about the Jewish community that once flourished in his homeland. In fact, a whole industry has emerged in recent years resulting in the laying of ‘stumbling stones’ (or stolpersteine in German), which are embedded on the streets by the houses in which the Jews lived.

These are further proof of ordinary Germans’ concern for their collective history, and that their Jewish neighbors should not be forgotten. Eighty years after the Holocaust, these stones represent more than just a reminder of the atrocities committed then, but are in a sense a mea culpa that the Germans themselves should never forget what was done in their name.

“Is there a difference in how the older generation remembers and how the younger one remembers?” asks Schreiber. “Zeh, for example, began to extensively reconstruct our family’s history. He searched archives, read books, scoured the Internet, and made contact with the youngest family members who once spent their childhood in Sassanfahrt, near Bamberg, Bavaria.”

Not that Schreiber needed reminding. As a second-generation child of Holocaust survivors, the war was very present growing up. The death of a survivor aunt and the discovery of family letters provided the real impetus for her own artistic exploration of her family history.

Zeh’s research, however, brought 14 Merel family members from England and Israel to Sassanfahrt in October 2017, for the laying of Stumbling Stones, in commemoration of Samuel and Minna Merel. Besides the stumbling stones, Zeh’s research also resulted in a short German publication of the family history, along with additional film material (there was very little to go on).

The memoirs of Sophie Merel (born 1929 in Schwabach) and Jenny Merel (born 1931 in Sassanfahrt) had already been published sometime before Zeh’s work Some 10 years earlier, Ruth Schreiber, the daughter of Nathan Merel (born in Leipzig in 1924), who was born in England after the Shoah, began her artistic project weaving together memories of her family history. Zeh found out about this and contacted Schreiber.

These materials are the sources of Schreiber’s current exhibition in Sassanfahrt, which opened on November 7. The year 2021 marks the 1,700 anniversary of Jewish life in Germany, and the exhibition will fall under the umbrella of this Germany-wide series of events. The exhibition includes 72 of 200 life-sized paper masks, a table set with plates, and texts drawn from the letters. There is in addition a short video called One Man’s Journey.

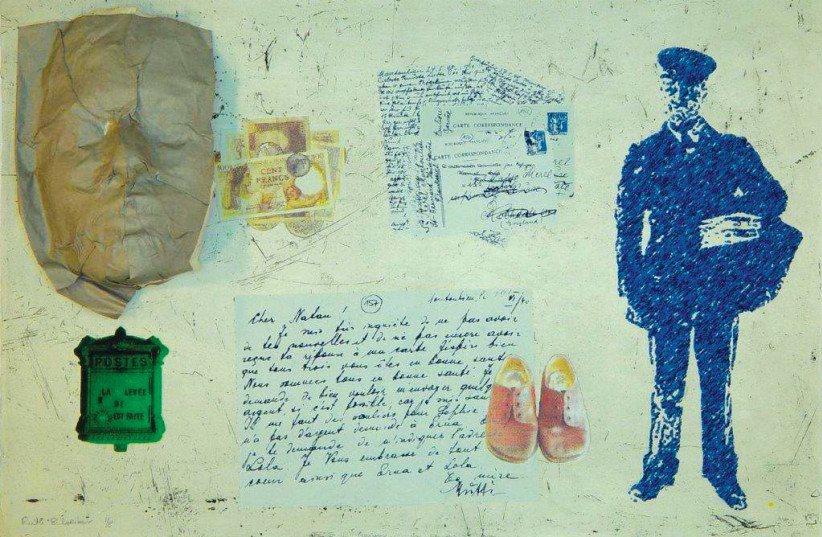

There are a number of sculptures including a two-meter-high mixed-media piece “Grandfather Samuel.” There are also ceramics and fabric art dedicated to Schreiber’s ancestry; a set of eight screen prints based on the letters, and an illustrated poem by the artist. There are four drawings based on the few surviving family photographs, a couple of small bronzes, and a ceramic sculpture of the “thumbs-down” sign, which was used in Auschwitz on the way to the gas chambers.

There is also a recording of a man and woman reading from the letters in German, Hebrew, French and English. Finally, there is a photograph of the ceremony held in 2017, in Sassenfahrt, where the stumbling stones were laid to perpetuate the grandparents’ memory.

This Holocaust Remembrance Project has engaged Schreiber for a number of years. In preparation for this massive undertaking, she had all the letters and postcards translated in 2010, and produced a book of the translations alongside family photographs and background material.

AT THE end of the 19th century, the majority of the world’s Jewish population lived in multi-ethnic Eastern Europe. From the 1880s onward, large numbers of Jews migrated from Eastern Europe to the West. The German Reich was a transit region on the way to the “New World.” However, some did not move on to North America, but settled in the German Reich. Among these were the Merel family.

Samuel and Minna Merel (née Feniger), who had come separately from impoverished Galicia, initially lived in Leipzig, where they married in 1920. Later they moved to Schwabach before continuing to Sassanfahrt. There they raised five children: Lotte, Esther, Nathan, Sophie and Jenny.

In the 1930s, they were the only Jewish family to reside in Sassanfahrt. Nevertheless, they had family ties in the region. Part of the paternal side of the family already lived in Bamberg, which had a small but vibrant Jewish community. Samuel, too, had tried to settle in Bamberg with his wife and children but failed.

As a Polish citizen, he did not receive a residence permit. In Sassanfahrt the isolated but traditionally Orthodox Merels belonged to the Jewish community in neighboring Hirschaid.

Everything changed with the rise of the Nazi Party in the 1930s. Esther and Nathan were sent to England on a Kindertransport from Nuremberg on January 5, 1939, at the age of 16 and 14, respectively. Though thousands of children were rescued this way, at least a million and a half Jewish children were murdered during the Shoah.

Like many other Jewish children from the German Reich, Esther and Nathan were initially sent to Dovercourt Camp near Harwich. The eldest sister, Lotte, managed to escape to England in early June 1939, where she trained as a nurse. Schreiber also learned recently that the number of children allowed into England during this period was deducted from the number of Jews allowed into Palestine by the British.

The parents and their youngest children, Sophie and Jenny, fled Franconia to Belgium in 1939, and then on to southern France in 1940. Soon after, they were interned in camps. Minna died in May 1941 in the hospital of the Le Vernet internment camp in the French Pyrenees, and was buried in a marked grave in nearby Perpignan. In 1979 she was re-interred by her son, Nathan, in the cemetery on the Mount of Olives.

The father, Samuel, after being sent to various work camps, was murdered in Auschwitz in August 1942. Until his murder, he continued to send letters and postcards to his children in England. These letters, all 200 pages of them, were preserved and are now archived at Yad Vashem.

In the letters, it was revealed that he had two opportunities to escape but would not leave his wife and small daughters. The two girls, at the age of 11 and nine, were rescued by a Jewish aid organization, the Osé, and kept in several children’s homes until they were smuggled over the border to Switzerland in 1943. Miraculously, all five siblings survived the War.

They met up again in London in October 1946. Schreiber’s father, for example, had studied in Schneider’s yeshiva in Germany, and when that yeshiva moved to London, they met up again. He studied optometry at night school, a profession that was vital during and after the war, and worked at this for many years. He then changed his profession and became a timber merchant.

After his wife (Schreiber’s mother) died in 1977, he began to publish books of Jewish rabbinical interest. In all, he published 15 books before he died in 2015. He and his wife had made aliyah in 1977. In preparation for his aliyah, he retrained in optics at which he worked part-time in Israel for 12 years.

The two older sisters moved to the USA while the younger two remained in London before emigrating to Israel, where they live in Jerusalem. Schreiber has spent 25 years raising her family and working in research, art and design. She has been developing her own work as an artist, and now creates sculptures, paintings, video art, photography and installation pieces.

She is a volunteer guide at the Israel Museum, a member of the Agripas 12 Co-operative Gallery in Jerusalem, and has exhibited and sold her art in Israel, Europe and North America. She has now gifted this art project to Hirschaid for permanent exhibition in the soon-to-be-renovated Jewish Community Center there, which she notes is in the same building where her father attended cheder (religious school).