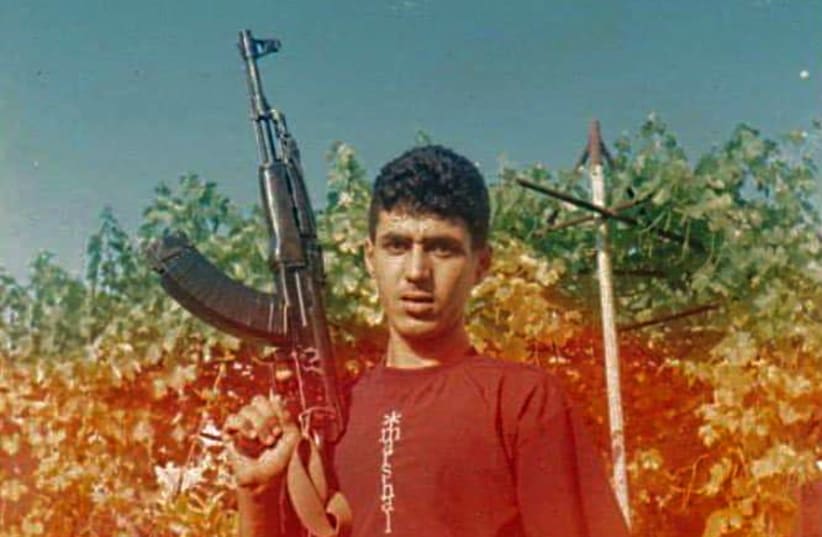

How does one go from being a rock-throwing child and a Kalashnikov-toting adolescent to being a voice for peace and negotiation in adulthood? Mohammad Massad, 46, made such a journey from Jenin to Haifa, now a voice of sanity asking the world to recognize the true oppressors of the Palestinians.

In 1975, Mohammad Massad was born in a village about five km. from Jenin. This was one year after the PLO was recognized as the official representative of the Palestinian people and only eight years after Israel won control of Judea and Samaria. The humiliation of defeat and their sense of the injustice of Israeli control could only be overcome by fighting back against the Jewish enemy.

This was the reality into which Mohammad was born, and by the time he was seven years old, he was throwing rocks at Israeli soldiers.

In contrast with the general sense of despair around him, he describes a home environment characterized by dignity, love and respect.

Mohammad attributes his self confidence and inner strength to his father, grandfather, a cousin and a male neighbor. A recurring theme, when talking about the men who influenced him, is the way he was treated with respect and how they commanded the respect of others.

I asked Mohammad about his mother. “She has a big heart and so much love,” he replied. She made us feel important. All of us feel equally loved by her and she made sure we all take care of each other.”

Induction into terror

Mohammad remembers how, when he was six years old, Nasser Kamil, 25-year-old former security prisoner and member of the PLO, assembled young children in the neighborhood.

“He would take care of us and play all kinds of games with us. He taught us songs against Israel and I remember in particular a song of love toward Yasser Arafat. Nasser wanted to keep us from playing in the street and getting hit by a car. He kept us from doing crazy things but we were living in the middle of ‘crazy.’” Mohammad was in second grade when the first demonstrations took place and he recalls having taken part in them. “I remember my mother’s words. She told my father: ‘when he grows up, we will need a lot of money to pay for his lawyers.’” And this was said with pride.

Kamil was arrested by Israel, and Mohammad considered it his duty to carry on with his activities.

From age 13, another former security prisoner had an impact on him. This time it was a cousin, one who was, and still is, a leader in Fatah.

“At the beginning of the first intifada I asked him to let me in on operations – the most difficult operations. He was wanted by the IDF and had status in the whole region. The fact that he was my relative gave me status as well. I wanted to be like him.” Mohammad was a founding member of the Jenin branch of the Black Panthers. They threw Molotov cocktails and grenades at IDF vehicles and burned tires. Bomb maker Yahya Ayyash, known as “The Engineer”, invited them to join in with Izzadin al-Qassam Brigades suicide attacks. Massad and his peers declined, saying that they are willing to risk death to achieve their goals but they are hoping to live.

In 1991, at the age of 16½, Mohammad and four members of the Panthers pulled over an Israeli car; two members of the group held the driver and the rest drove around looking for an Israeli soldier to abduct to exchange for Palestinian prisoners being held in Israel. They were spotted by Israeli security forces and forced to abandon the car and run back behind the border.

He was arrested by the IDF after that incident. After 45 days of interrogation, he admitted to activities that were, in any case, known to all: “I gave them what they already knew.”

Torture in the Israeli jail included sleep deprivation, being kept in a room the size of a closet, and being forced to stand all day with his hands tied to a pipe above his head. The ceiling was a grate that kept him exposed to the rain and sun with nothing to protect him from the cold of approaching winter. Mohammad said they did not beat him – “there were a few slaps, nothing serious.” They cursed and humiliated him, but he expected this as they were the enemy and that is how the enemy is expected to behave.

He was sentenced to seven-and-a-half years in prison. To the prosecution this was too light and they appealed. About two years after his arrest, however, before the appeal, he was released as part of the Oslo Accords. “I got off easy.” Upon his release he was invited to join the Tanzim, the military arm of Fatah. Responsible for his village, he served as a bridge between local villages and the high ranking leaders of the movement.

However, he now faced a new and shocking reality: far from the open democratic independent society he and others like him thought they were hailing when they jubilantly welcomed Arafat, Massad found a new regime characterized by brutality and injustice. No criticism of the new Palestinian Authority was allowed, and debate was suppressed violently. For example, PA security forces stormed An-Najah University campus in Nablus and savagely beat students who voiced opposition to Oslo and the PA.

Criticism against the PA was openly expressed in the Massad family. They were upset with the corruption and suppression they saw. Mohammad’s father would say: “they are riding on the backs of our people.”

Mohammad left the Tanzim and began working illegally in Israel in a number of jobs, including construction. One day he was asked to come in to the police station in Jenin. Thinking nothing of it, he showed up a few days later. To his surprise, he was immediately arrested and thus began 23 days of torture and investigations. He was accused of collaboration with the Shin Bet (Israel Security Agency).

“Each day of interrogations by the PA was harder than all 45 days together in Israel. They beat me with anything that came to hand. They insulted the honor of my sisters and mother with curses. I expected the Israeli enemy to humiliate me, but those I had helped bring into the land over the dead bodies of my friends, I did not expect them to humiliate me or my family. This was unbearable. Before the Israeli applies physical force, he gets permission and makes sure the prisoner can tolerate it and it is according to the law. But here was a mafia running things.” At the same time, he felt the pain of the other prisoners. As he sat in his cell between interrogations he heard the cries of others being beaten.

“They would beg them to stop and I felt sorry for them. When they beat me, I threatened them. Told them I would make them pay for what they are doing to me. So I felt sorry for those who were weaker. They had no courage to tell the interrogator that he should interrogate himself first. ‘I need to interrogate you,’ I would say.” He understood that he was being used to show others in his community that protesting the PA makes them suspected traitors, collaborators.

Finally, after 23 days his interrogators had to admit that he was innocent.

“They apologized to me and to my family. But I will never forgive them. I was able to stand up to them because I am honest and strong, but others – after two slaps – will confess to anything just to avoid more beating. You just want to stop the pain, so if someone is told: you killed 20 people, he will say he killed 22, just to end the torture. After this, they execute him and claim he confessed.” In this environment, many gangs emerged who took advantage of the lawlessness. There were those who collected money claiming that it was for the purposes of freeing the land. But it was, in fact, protection money. Anyone who did not contribute was accused of being against the regime.

“When I understood that those I was ready to die for had brought corruption, alcohol, prostitution and oppression of the people, it was as if I had been struck by lightning.”

Israeli citizenship

“My luck is that I had not killed anyone. I burned vehicles but I take it as a sign that God loves me that nobody died – no Jew and no Arab. While I was a member of the strongest terrorist group, nobody got hurt by me. I even stood in front of an IDF jeep and shot at it, but it was not written that I was to die that day.” Mohammad continued to sneak across the border into Israel and work at various jobs. At one point, he married an Arab-Israeli woman and applied for citizenship. By this time, he was a contractor and hired illegals himself.

One day, when waiting at the border for his workers to come across, he spotted a terrorist a few hundred meters from him. The terrorist assaulted a solitary soldier near the fence, knocking him down and wrestling to take his rifle from him. Mohammad rushed up and chased him away, saving the soldier’s life and his weapon. For this, he was awarded a Certificate of Appreciation from the IDF. His pathway to Israeli citizenship was now a sure thing.

Mohammad Massad now lives in Haifa, married for the second time. He is involved in the lives of all his children and supports his first wife, who lives nearby. He is currently working toward a masters degree in Middle East Studies at the University of Haifa.

For many years, he has been working behind the scenes to help develop the foundations of the democratic free society that he anticipated would arise when he was a Black Panther fighting Israel and that he hopes will still arise. Recently, he was appointed as head of the Palestinian Workers’ Organization, and is the voice opposing their exploitation by the PA. He avails himself of the Israeli legal system in attempts to bring justice to the Palestinian people. And he anticipates the fall of the PA.

When he was a Black Panther terrorist, Mohammad Massad was fighting for truth and justice as he saw it. He is still doing that now.

“I feel obligated to my people who need me. If we free our people from fear, you will see something very different.”