In the popular television series Curb Your Enthusiasm, known for its “edgy” humor, Larry David plays a fictional version of himself, a successful Jewish television writer living in an affluent Los Angeles neighborhood with a beautiful non-Jewish wife.

In “The Baptism,” Larry’s sister-in-law has invited Larry and his wife to witness her fiancé’s baptism as part of his conversion from Judaism to Christianity before their marriage. Larry and his wife are late getting to the baptism, which is taking place at the side of a stream near his sister-in-law’s house. Larry, seeing a man pushed into the water, jumps into the stream to save him and ruins the ceremony.

Back at his at his sister-in-law’s house with the other guests Larry is contrite. However, the Jewish guests let him know that they are proud of his action. Meanwhile, the fiancé announces that he has decided to remain Jewish and this leads to a heated exchange, with a voice on the Jewish side saying “we resent the recruitment” and someone on the other side saying “we didn’t know you were so sensitive.” I was reminded of this episode and the issue of proselytization when I read an exceptionally forthright and sensitive article titled, “Us vs. them: Challenging stereotypes about Judaism in the wake of the Pittsburgh shooting,” published on November 1, 2018, by the University of Washington Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. In it, Mika Ahuvia addresses a core issue governing relations between Christianity and Judaism, that of supersession (or replacement theology). In supersession thinking, Judaism stopped developing in the first century CE and the New Testament has superseded the Old Testament. Moreover, the God of the Old Testament is a vengeful God and Judaism is a legalistic religion that emphasizes ritual as compared to the emphasis of love and compassion in Christianity.

In fact, while Jews may read and respect the New Testament, the New Testament does not have a monopoly on compassion. Moreover, the Jewish way of life was attractive to others and, as Ahuvia notes, “That is why Paul railed against gentiles adopting the Law (i.e. the Torah) in the Letter to the Galatians.”

In other words, Judaism and its rituals, such as the dietary laws, circumcision and the keeping of the Sabbath, must have had some appeal to the recipients of Paul’s letters.

In Constantine’s Sword (2001), James Carroll makes the same point in noting that in 315 CE, just two years after Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire, proselytization by Jews to non-Jews became illegal. Later, it became a capital offense. These actions were in response to the success Jews were having in attracting Christians to Judaism. After 315 CE, those who converted to Judaism did so at their own peril.

To be clear, modern-day Judaism does not sanction proselytization and when Ahuvia and Carroll comment on non-Jews being attracted to Judaism they are not referring to the aggressive form of proselytization that has characterized Christianity (and Islam). The key difference is the Jewish belief that righteous non-Jews will also have a place in the World to Come.

However, over the centuries Jews have been the targets of repeated and well-documented efforts to convince them to convert to Christianity, either by force or persuasion. The question now is how Christians view proselytization to Jews today.

In 1965, and as what Paul Johnson (A History of the Jews, 1987) refers to as moral reparation by the church for its contribution to Jew-hatred, Vatican II issued Nostra Aetate (Declaration of the Relations of the Church to Non-Christian religions), stating that not all Jews, then or now, are responsible for the death of Christ. While “the Church is the new people of God, the Jews should not be represented as rejected of God.” This is certainly an important step, but both Johnson and Carroll (Constantine’s Sword) describe it as a ‘grudging’ document, which makes no apology for the church’s persecution of the Jews.

Fifty years later, in 2015, the Vatican Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews issued a document, under the papacy of Pope Francis, titled “The Gifts and the Calling of God are Irrevocable – A Reflection on Theological Questions Pertaining to Catholic–Jewish Relations on the Occasion of the 50th Anniversary of Nostra Aetate.”

Nostra Aetate, a relatively short document of about 1,600 words, addresses other non-Christian religions as well as Jews. By contrast, the 2015 document is a far-reaching and comprehensive historical review of Jewish-Catholic relations, particularly from Vatican II onwards. It also refers to the history of forced conversion of Jews to Christianity, supersession theology, as well as to the Shoah and to the Church’s relationship to the State of Israel.

The document draws attention to an earlier 1980 statement by Pope Paul II that Jews do not need to convert to Catholicism to find salvation since God did not revoke his covenant with Israel. Most importantly, the 2015 document states “the Catholic Church neither conducts nor supports any specific institutional mission work directed towards Jews.”

The 2015 document received widespread press coverage and expressions of appreciation by a number of Jewish organizations. A week before the Vatican document was released, two dozen Orthodox rabbis signed a “statement on Christianity” circulated by the Israel-based Center for Jewish-Christian Understanding and Cooperation.

The statement includes the following: “Now that the Catholic Church has acknowledged the eternal covenant between God and Israel, we Jews can acknowledge the ongoing constructive validity of Christianity as our partner in world redemption, without any fear that this will be exploited for missionary purposes.”

What of the other Christian churches? Here the situation is less clear because of the absence of the hierarchical structure of the Catholic Church. For example, while a 1995 statement by the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada expresses respect for the Jewish people and remorse for the role of Martin Luther’s antisemitic writings in fostering violence against Jews, a 2014 article in The Washington Post by Lily Fowler highlights the efforts by members of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod to convert Jews to Christianity.

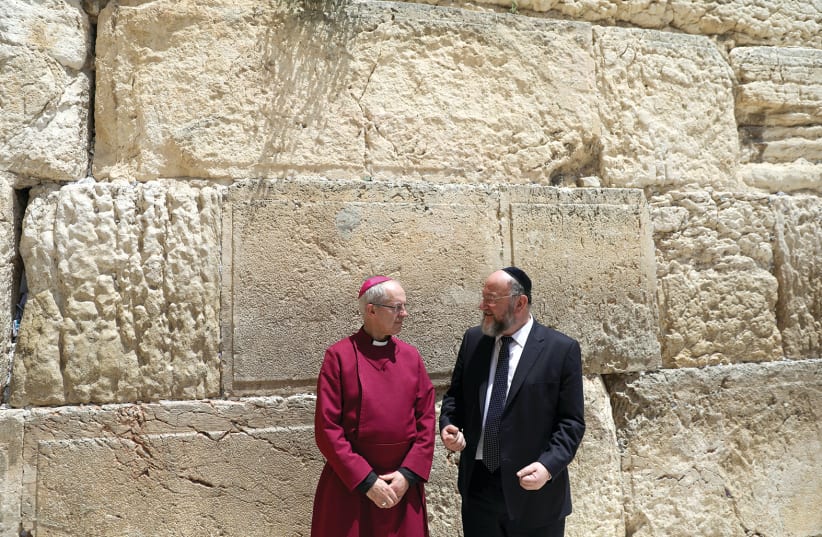

The Anglican Church provides another example. In 2019, the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada approved the removal from the Book of Common Prayer of a prayer calling for the conversion of Jews. (The change requires ratification by the next General Synod in 2022). A new prayer titled “For Reconciliation with the Jews,” formulated after extensive consultation with a wide range of clergy and theologians, including the Canadian Rabbinical Caucus, will replace the old one. The new prayer is a remarkably sensitive prayer of repentance and interfaith respect and fellowship. It includes the statements: “Have mercy upon us and forgive us for violence and wickedness against our brother Jacob.” and “Take away all pride and prejudice in us, and grant that we, together with the people whom thou didst first make thine own, may attain to the fullness of redemption.” Also in 2019, the Church of England, the mother church of the International Anglican Communion, issued a 121 page document titled “God’s Unfailing Word: Theological and Practical Perspectives on Christian–Jewish Relations.” This statement provides a detailed review of the history of Christian-Jewish relations, including the Christian role in the long saga of Jewish persecution, up to and including the Holocaust. It expresses considerable understanding of Jewish concerns and perspectives, including the role of and importance of Israel to Jews. It notes that in 2018 the Church of England’s College of Bishops accepted the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance definition of antisemitism, which includes denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination, However, in spite of noting Jewish sensitivity to missionary activity, and in contrast to the 2015 Vatican statement, the document does not rule out such activity, a fault pointed out in the Afterword by Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis, the chief rabbi of the UK. Mirvis states “even now, in the twenty-first Century, Jews are seen by some as quarry to be pursued and converted.” In his 2018 book 21 lessons for the 21st Century, Yuval Noah Harari portrays Judaism as a tribal creed with limited impact on the world, not a universal religion like Christianity. While he admits that without Judaism we would not have Christianity, he suggests that it is like saying that without Sigmund Freud’s mother we would not have had Freud. In other words, Freud’s contributions to modern Western society had little to do with his mother.

I do not agree with Harari and I doubt that Mika Ahuvia or James Carroll would. Christianity may be a universal religion but its story is largely dependant on a tribal story. I believe that this relatedness has led to replacement theology, and the need, by some, to proselytize to Jews. As Carroll points out, Judaism exists without reference to Christianity, but the reverse is not true. “The God of Jesus Christ, and therefore of the Church, is the God of Israel.” Ahuvia counsels Christians to have confidence in Christianity, without needing to put Judaism down, while Jews should appreciate their own traditions, without needing to justify themselves to others. She adds “The other will remain other, but we have the choice of choosing between love or hate as our point of departure.”

The writer is a distinguished professor emeritus at the University of Waterloo