Insofar as the 1980 law does not specify the boundaries of the Jerusalem municipality, the US is in agreement. When former US president Donald Trump recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital in December 2017, and was roundly condemned by much of world opinion for doing so, the words he uttered at the same time are rarely quoted.

“We are not taking a position on any final status issues,” said Trump, “including the specific boundaries of Israeli sovereignty in Jerusalem... Those questions are up to the parties involved.” Subsequently, when Trump finally unveiled his Israel-Palestinian peace plan in February 2020, he explained that it envisages a Palestinian capital in eastern Jerusalem to be called Al Quds, where the US will “proudly” open an embassy.

International opinion disagrees with Israel over the status of Jerusalem. The reaction of the UN Security Council to the Jerusalem Law of 1980 was to adopt Resolution 478, which condemned the assertion of Israeli sovereignty over east Jerusalem as a violation of international law and called upon UN member states to withdraw their diplomatic missions from the city. That advice stretched logic to breaking point. The 13 national embassies concerned were sited in west Jerusalem, whose status was unaffected by the 1980 law. The recommendation to relocate them seemed perverse. Nonetheless, in the end all moved to Tel Aviv.

The UN’s position on Jerusalem is an object lesson in illogicality. “Jerusalem is a final status issue,” declared Nickolay Mladenov, UN special coordinator for the Middle East peace process, in the session of the UNSC that considered Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and his decision to move the US embassy there. “A comprehensive, just and lasting solution must be achieved through negotiations between the two parties, and on the basis of relevant UN resolutions and mutual agreements.”

In other words the UN holds that the exact status of Jerusalem in international law is as yet undetermined. Yet the UNSC, in its Resolution 2334 passed in 2016, had no doubts on the subject. The status of Jerusalem and the West Bank, it determined, was at it had been on June 4, 1967 – that is, on the day before the Six Day War commenced ‒ referring three times to “Palestinian territories including East Jerusalem.”

So the UN asserts that Jerusalem’s status is yet to be resolved and in the same breath that east Jerusalem is Palestinian territory. It does not acknowledge that on June 4, 1967, west Jerusalem was Israel’s capital. Even less understandably, it ignores the fact that Jordan, having conquered the West Bank and east Jerusalem in its attack on Israel in 1948, proceeded to annex them in a move not recognized by the UN or any other international body, nor by any countries except the UK and Pakistan. When Israel recaptured them in 1967, logic suggests that their true status was that they were being held illegally by Jordan and, in international law, were the sovereign territory of no nation. The UN, however, maintains that they were Palestinian territory.

Even before Trump formally recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital in December 2017, Salva Kir, president of the newly independent state of South Sudan, told a visiting Israeli delegation in August 2011 that he planned to locate his embassy in Jerusalem. Later that year, Kir visited Israel to express his gratitude for its support during the civil war. At a meeting with Israel’s then-president Shimon Peres he reiterated his intention. That wish has not yet proved father to the deed.

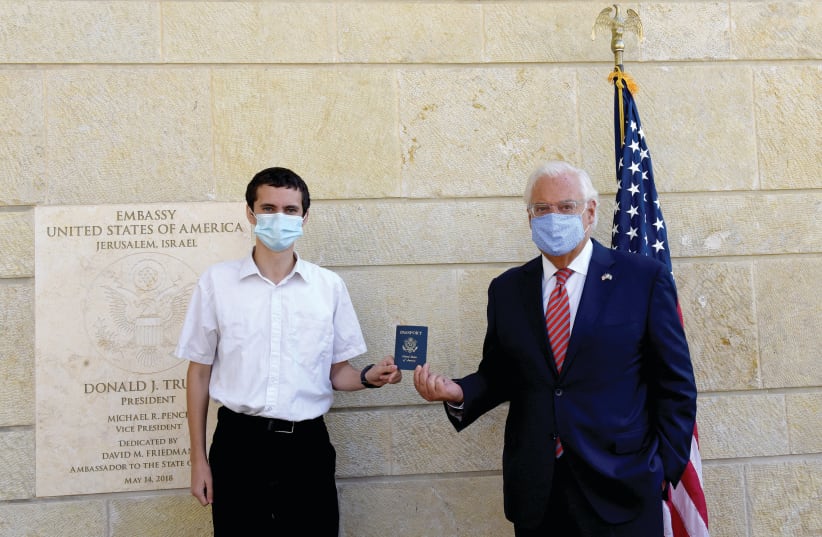

It was in July 2016 that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu undertook an historic tour of east Africa. Some of the fruits of his journey became apparent in May 2018, when no less than 12 African heads of state attended the ceremony relocating the US embassy to Jerusalem. Since then, reports – some of them solidly based, others rather less substantiated – have been swirling around the media naming one African state after another as being on the verge of following the US’s example.

In February 2020, Uganda was reported as “mulling” its intention to do so. In September, attention had turned to Malawi. By November it was Rwanda. On February 19, 2021 Equatorial Guinea announced its intention to relocate its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

The rumors were far from confined to African states. Central and South American nations also featured. In April 2018, Brazil was in the spotlight, together with Guatemala ‒ and then, for once, the whisper became reality. On May 16, 2018 ‒ two days after the US formally relocated its embassy to Jerusalem ‒ Guatemala followed suit. Later that month, media rumors focused on Paraguay and Honduras. In December, it was the Dominican Republic.

December 2018 also saw a major news story featuring Australia’s new prime minister Scott Morrison, who went on the record announcing that Australia would consider following the US and move its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. He said it may be possible for his nation both to support a two-state solution and also recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital ‒ something that Australia had “to date assumed” was unfeasible. His statement drew a tweeted response of approval from Netanyahu. So Australia joined the ever-growing list of nations with this embassy issue simmering on its back-burner.

European nations were not spared by the headline-seeking media machine. Shortly after Trump’s announcement, the Czechs declared that they viewed Jerusalem as the “capital of the State of Israel, in its 1967 borders.” In other words, they rejected the UN’s equivocation but restricted their recognition to West Jerusalem. In April 2018 the Czech ministry of foreign affairs announced that the Czech government intended to open an honorary consulate and a new Czech Center in west Jerusalem. Relocating its embassy from Tel Aviv would seem the next logical step in the Czech Republic’s leisurely journey.

At about this same time, sections of the government in Romania were reported to be in favor of moving the Romanian embassy to Jerusalem. Next in the frame were Serbia and Kosovo, and in this instance substance followed rumor.

It was on September 4, 2020, in the White House that Serbia and Kosovo signed a US-brokered agreement, counter-signed by Trump, to normalize economic relations between them. The agreement went wider. It included plans for Israel and Kosovo to establish diplomatic relations between each other, and for Serbia to move its Israeli embassy to Jerusalem.

“After a violent and tragic history and years of failed negotiations,” said Trump, “my administration proposed a new way of bridging the divide... By focusing on job creation and economic growth, the two countries were able to reach a major breakthrough.”

In February 1998 Kosovo, a Muslim province of the old Yugoslavia, attempted to break free from Serbia and Montenegro. The dispute soon degenerated into armed conflict. It was a particularly brutal struggle, into which NATO finally intervened to protect Kosovan civilians. The war ended with a treaty under which Yugoslav and Serb forces withdrew to make way for an international presence. Kosovo declared itself an independent state in 2008, but Serbia refused to recognize it, and in fact continues to regard Kosovo as a province of Serbia.

Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic and Kosovar Prime Minister Avdullah Hoti both considered the White House agreement a significant development. “Of course,” said Vucic, “as regards the politics we haven’t resolved our problems. There are still a lot of differences between us, but this is a huge step forward.”

The White House deal also set the seal on mutual recognition between Kosovo and Israel, and as part of the arrangement Kosovo promised to open an embassy in Jerusalem, and Serbia undertook to move its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, both by the summer of 2021.

On February 1, in a ceremony held over Zoom in Jerusalem and Pristina, Israel and Kosovo formally established diplomatic ties. By doing so Kosovo became the first Muslim-majority country to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. If the full terms of the White House deal are met, Kosovo will be the first Muslim country to have a Jerusalem-based embassy, and only the third nation after the US and Guatemala to have one. Serbia will be the first European country to open an embassy in Israel’s capital.

Meanwhile UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres finds himself in something of a bind. He cannot but welcome the recent agreement between Serbia and Kosovo, and the establishment of diplomatic relations between Kosovo and Israel, yet the decision of Serbia and Kosovo to site their embassies in Jerusalem is a direct violation of UN Resolution 478, which advised all nations to withdraw their embassies from the city.

The press briefing conducted on September 14 by Stéphane Dujarric, spokesman for the secretary-general, illustrates the embarrassing dilemma. Asked how the secretary-general views moving embassies to Jerusalem in the context of moves toward peace, Dujarric welcomed countries recognizing and establishing relations with each other, while the location of its embassy was a decision for individual states. As for the status of Jerusalem, he repeated the well-worn mantra that it was an issue to be decided by the parties.

This did not satisfy the media corps, one of whom pointed out that siting an embassy in Jerusalem was in direct violation of Resolution 478, but Dujarric refused to be drawn.

The embassy barrier imposed by the UN is obviously breaking down. Sooner or later, other nations who have indicated an interest in resiting their embassies in Israel’s capital will act. One determining factor may well be the strong bipartisan support evidenced in the US against reversing Trump’s embassy move. On February 4, the US Senate voted 97-3 in favor of keeping the US embassy in Jerusalem. That this was the position of US President Joe Biden’s administration was confirmed by new US Secretary of State Antony Blinken during his Senate confirmation hearing, when he also said that the US would continue to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

The rumor mill has been busy on this issue. Over the past few years at least 14 nations have been identified in the media as possible candidates for locating or relocating their embassies to Jerusalem. Some are merely the subject of a whisper; others have indicated a firm intention of doing so, but have not yet matched their intention with action. The record shows that the names in the frame are: Equatorial Guinea, South Sudan, Brazil, Moldova, Romania, Paraguay, Honduras, the Czech Republic, Uganda, Serbia, Malawi, Rwanda, the Dominican Republic and last, but by no means least, Australia.

The potential field is, of course, far larger. Israel enjoys diplomatic relations with more than 160 countries, virtually all of which have sited their embassies in Tel Aviv or neighboring cities. A wholesale relocation of these foreign embassies is unlikely ‒ unless or until a Biden-inspired peace negotiation finally determines the extent of Israeli sovereignty in what is now the Jerusalem municipality. Once the position is clear, accepted by all concerned and endorsed by international opinion, everything else will follow.

The writer’s latest book is ‘Trump and the Holy Land: 2016-2020.’ He blogs at www.a-mid-east-journal.blogspot.com