In this case, not only am I acquainted with Isi Leibler, but have known him for most of my life, both in Australia and in Israel.

When he was still a young community activist, he was one of the first leaders of Australian Jewry whom I interviewed early in my career as a journalist. In the interim, I have either interviewed or written about four generations of his family in which leadership seems to be a genetic characteristic on both sides as well as in the family of his wife Naomi, née Porush, whose Jerusalem-born father, the late Rabbi Israel Porush, was chief rabbi of the Sydney Great Synagogue for almost 33 years, and for 23 years served as the president of the Association of Jewish Ministers of Australia.

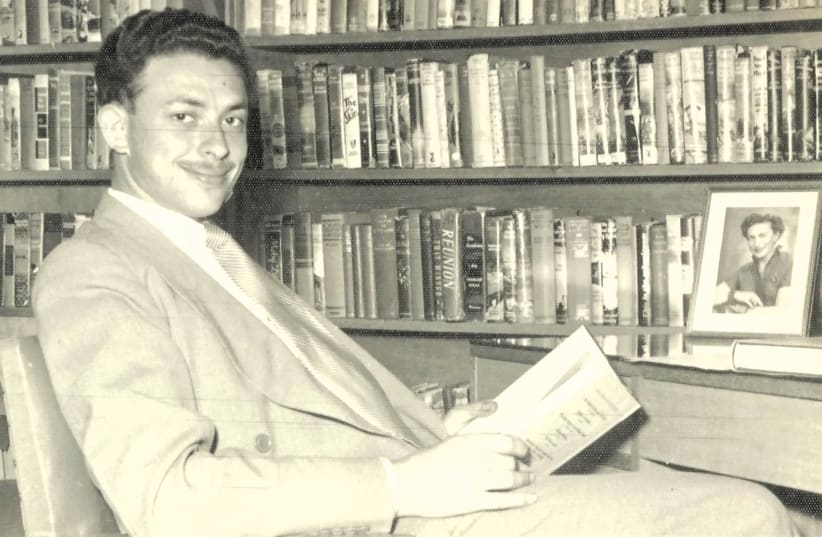

Isi Leibler, 86, is the subject of a new, beautifully written and comprehensive book by historian Suzanne D. Rutland. The book is the culmination of 20 years of research from more than 80,000 pages of documentary evidence. It is something she would have been unable to manage without the assistance of former Jerusalem Post op-ed editors Elliot Jager and Judy Montagu, she acknowledges.

Mark, the older of Leibler’s two younger brothers, is a leader of Australian and world Jewry in his own right. A biography of Mark Leibler, The Powerbroker, by noted Melbourne journalist Michael Gawenda was released in July.

Rutland’s warts-and-all book is infinitely superior. Unlike a previous book, Let My People Go, that she wrote in 2015 with widely acclaimed Australian Jewish journalist Sam Lipski (a lifelong friend of Leibler’s), which tells the story of Isi Leibler’s courageous and often dangerous battle on behalf of Soviet Jewry, this new book does not read like an academic work.

For Australians, and Melbournites in particular, it is definitely a page turner, with footnotes being the only concession to academia and to Leibler himself, who according to Rutland did not interfere with the contents other than to correct a spelling mistake or a misinterpretation. But he wanted readers to know the source of what was written, she explained.

As for his voluminous and meticulously arranged archives, Rutland attributed this material not only to the secretaries who nurtured them, but also to Leibler’s photographic memory. After every meeting, he wrote down what had transpired. His notes were later transcribed and placed in color-coded files depending on the subject matter.

The preface to the book is written by former Supreme Court justice, attorney general and peace negotiator Elyakim Rubinstein, who met Leibler in the late 1970s when Rubinstein was the legal counsel for Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Rubinstein mentions the different aspects of Leibler’s multi-faceted career, but in the context of family, also writes about how Naomi and Isi Leibler made a home for their respective mothers, Bertha Porush and Rachel Leibler, who each lived to a triple-digit age. It was heartwarming to see the two mothers living with them and sharing their Shabbat meals, Rubinstein said. “In our current world, this special kind of honoring parents is unusual,” he wrote.

This is the example the Leiblers showed to their own four children, all of whom live in Israel and have provided them with numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Naomi Leibler in her student days was president of B’nai B’rith Young Women, president of the Sydney University Jewish Students’ Union and vice-president of the National Union of Australasian Jewish Students. After her marriage, she was co-president of Emunah Aviv, and some years after settling in Israel, was elected president of World Emunah.

The book’s list of contents is a time line that begins with Leibler’s birth in Antwerp, his mother taking him out as a child just before Belgium capitulated to the Nazis, and continues through to the present day in which Leibler’s widely-read columns are published in The Jerusalem Post, Israel Hayom, the Australian Jewish media and elsewhere.

While the timeline provides a thumbnail biography, which is particularly interesting for people from Melbourne, where Leibler lived for some 60 years, the 12-and-a-half-page index in the back of the book is more of a fascinating study. I counted in excess of 180 names of friends, acquaintances, colleagues and people about whom I’ve written over the years, and I must confess delighted surprise at finding my own name on the list. Abe Feiglin, the founding principal of Mount Scopus College, where I was a student, was included, as were five of my former editors, the first of whom was Mannie Oderberg.

The chapters in the book are more thematically arranged than chronologically, which means that readers can start or continue with those subjects which appeal to them most, as if they were reading a short story.

In this sense, the book has something for everyone: Australian Jewish and general politics; the Jewish world; the Zionist enterprise; antisemitism; Nazi war criminals and their collaborators who slipped through the refugee cracks and came with Holocaust survivors to Australia; right wing radicalism; simultaneous fights against fascism and Communism; the building of a business empire; diplomacy; espionage; the struggle for Soviet Jewry; rubbing shoulders and shaking hands with world leaders; exposing corruption in the World Jewish Congress; Jewish media, family life and so much more.

In addition to his community, business and family commitments, Leibler is a voracious reader, collecting almost anything in the realm of Jewish literature. In this respect, he had what was arguably the greatest privately-owned Jewish library in the world. Unfortunately, his children were not interested in preserving it, so he endowed it to Bar-Ilan University.

Inasmuch as he earned many admirers and supporters along the way, Leibler also made some enemies and detractors. Never afraid to stand up and fight for what he believed to be morally and strategically the right thing to do, he sometimes managed to get his opponents not only to agree with him, but to publicly verify charges that he made. The best example is of Australian Communists – both Jewish and non-Jewish – who after reading in his booklet the detailed evidence he had collected on Soviet antisemitism, conceded that Moscow’s policy regarding the Jewish population was in violation of human rights. Some Communists were so disenchanted that they left the party.

When Leibler first came to Israel in 1957, he cherished the idea of staying and becoming a diplomat. The untimely death of his father dashed those hopes. There was no way that he could get back to Melbourne in time for the funeral, and so he followed his mother’s instructions to go to Antwerp and learn the diamond trade so that he could take over the family business.

Officially, he was never a diplomat. Professionally, he was a diamantaire and later the proprietor of the largest travel business in Asia and the Pacific. He was also a Jewish leader, both in Australia and internationally. It was as a successful businessman and a respected Jewish figure that he acted as an unofficial diplomat for Israel, first at the bidding of spymaster Shaul Avigur in matters pertaining to Soviet Jewry, and later at the behest of the Foreign Ministry’s Moshe Yegar and Reuven Merhav – who was then consul general in Hong Kong – Leibler helped to pave the way for the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Israel, and between India and Israel.

Although the book deals largely with Leibler’s life in Australia and his pioneering efforts to bring the discrimination and persecution of Soviet Jews to global attention, it also dwells on the challenges he faced and resolved both as a businessman and a Jewish community activist and leader. No less important was his exposure of corruption in the World Jewish Congress, which caused him public humiliation and personal embarrassment. But Leibler refused to buckle under the indignities that were heaped on him. Long before that Leibler had challenged Nahum Goldmann the long-standing founding president of the WJC who preferred quiet diplomacy on the Soviet Jewry front rather than the public outcries and demonstrations which to some extent were generated by Leibler. Curiously, Leibler’s home in Jerusalem is only a few buildings away from the one in which Goldmann had his apartment. While there is great virtue in being honest, it is often easier to be honest when one can afford it. As a wealthy individual, Leibler could well afford to be honest, both morally and financially. But one suspects that even without the affluence to bolster his access to high places, Leibler would always find a way to get to the right people to create awareness of whatever cause he was espousing at any given time.

He had incredible connections all over the world – partially resulting from his travel business, and partially from his leadership roles.

It should be noted that his leadership started when he was a youth in Bnei Akiva. He was in his early twenties when he returned from Antwerp to Melbourne and almost immediately became embroiled in community life and in corresponding with Jewish leaders and influential figures in international Jewish organizations. In those days, video conferences, email and mobile phones were not yet part and parcel of daily life. People wrote letters, and Leibler wrote many, several excerpts of which appear in the book.

Aside from letter writing, Leibler penned numerous articles and also wrote a couple of books, the first of which – Soviet Jewry and Human Rights – caused an international furor. The formidable Maurice Ashkenasy, who was Australian vice president of the International Commission of Jurists and who preceded Leibler as president of both the Victorian Jewish Board of Deputies and the Executive Council of Australian Jewry, subsequently wrote about Leibler when the latter was still 30 years old: “He not only makes history, but he writes and records it and in writing and recording it he makes more history.”

Jenni Frazer, in her review of the book for the London Jewish Chronicle wrote that “Lone Voice chronicles, in at times suffocating detail, the trajectory of the Antwerp-born Leibler, who made his fortune in the travel business in Australia, and made his name in his early feisty campaigning for Soviet Jewry.“

The book was researched and written by an academic and professional historian for whom every detail is a gem. Moreover, given the volume of her research and the time it took to transfer her findings into a book that could be enjoyed by other academics and lay people alike, any future researcher, historian or otherwise – who may be interested in writing about the life and times of Isi Leibler – will have to go no further than this book.

Lone Voice: The Wars of Isi Leibler

Suzanne D. Rutland

Gefen Publishing House

680 pages; $39.95