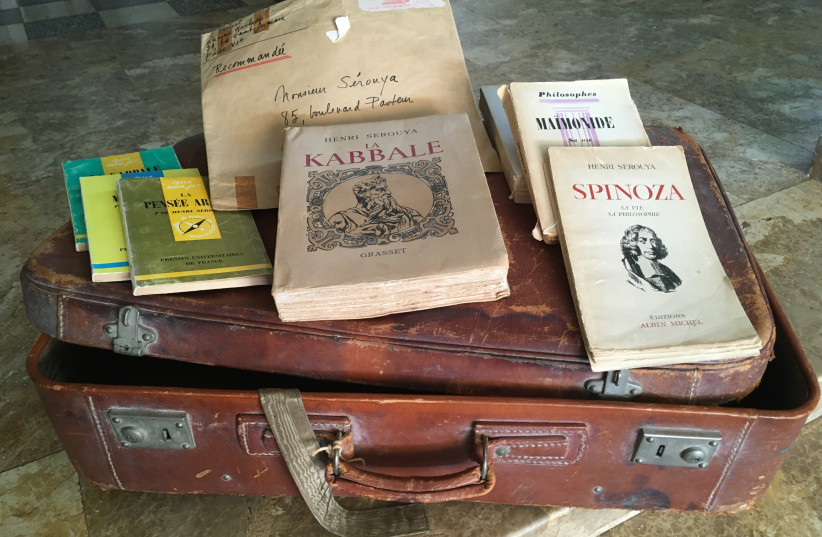

A battered old brown leather suitcase, crammed with an archive of letters, diaries, manuscripts, press cuttings, flyers – all in French – had for decades been gathering dust in the basement. It was the forgotten legacy of Henri Serouya, historian, intellectual, philosopher, author of many acclaimed books and learned articles, all in French. Among his subjects were Judaica, Israel, philosophy, Spinoza, Maimonides, the Essenes, fine art and the French/Jewish painters of l’École de Paris in the period between the two world wars.

Serouya came from a family of learned rabbis originating in Portugal. His parents came to Palestine from Aleppo in the late 19th century, and Henri, the youngest of their four children, was born in 1895 in Jerusalem. Here he was educated at the Alliance school where his outstanding talents were recognized and nurtured. In 1911, part of the family moved to Cairo, later to Cuba and then to New York. With support and grants from the Alliance center, Henri was sent to Paris in 1913 to continue his studies at the Sorbonne. He lived the rest of his life in France and became a French citizen in 1931. He left behind in Israel his sister and other relatives, with whom he remained in contact over the years. And that is how I got to know him, through my father-in-law, Joseph Manobla, Serouya’s nephew and closest friend.

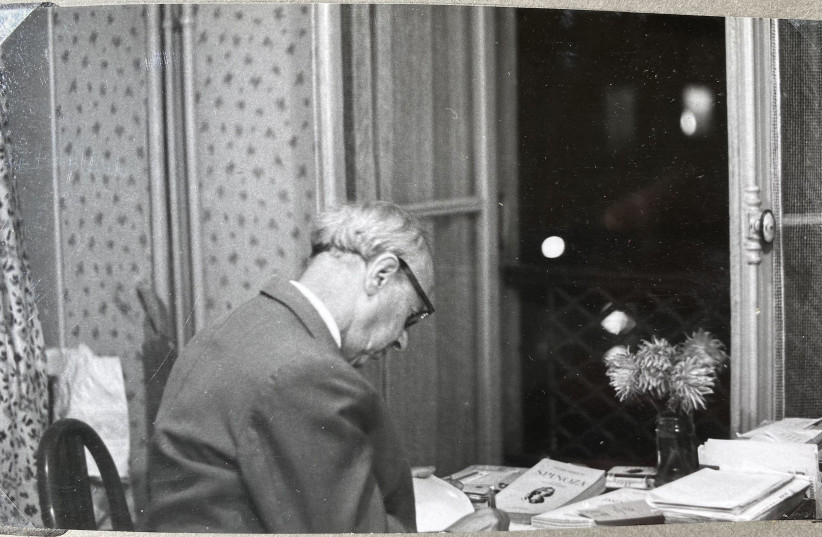

My husband and I met Uncle Henri when he came to Jerusalem for our wedding, his second visit to Israel since leaving the country. He had come in 1949 as a guest of the Israel government. In 1961 he stayed with us for some weeks. When he returned to Paris, I corresponded with him on behalf of the family, and the battered old brown suitcase contains my letters to him and letters from his nephew Joseph and other family members. On our honeymoon trip to Europe we visited him, and I photographed him at his desk, surrounded by books and manuscripts, in the modest Boulevard Raspail studio apartment where he lived until his death in 1968. Across the road are the famed coffee houses and restaurants of Montparnasse, still there, Le Dôme and La Coupole, unchanged to this day. In the 1920s and 1930s these were the gathering places for writers, intellectuals, Bohemians, and the famed artists of l’École de Paris school of painting.

Many of these artists were Yiddish-speaking Jews from eastern Europe, who rejected the shtetl and the narrow world of orthodox Jewry. Fleeing the tyranny and antisemitism of Tsarist Russia, they were drawn by the artistic freedom and the acceptance of foreigners found in early 20th century Paris.

Their center was La Ruche (the Beehive), an octagonal cosmopolitan residence in Montparnasse funded by wealthy patrons of the Bohemian artists and writers. It was here that Serouya found a congenial environment and a group of soulmates. The artists, most of them desperately poor, were united in their commitment to art and ready to support one another when needed. Few of them made a good living from the sale of their works.

Among those who did succeed and whose paintings today command astronomical prices, were Chagall, Modigliani, and Serouya’s friend Chaim Soutine, all Jewish.

IN THE years between the wars, Serouya and Soutine were very close, each admiring the other’s skills and talents. They went for long walks together, discussing books and paintings, art and philosophy. The German occupation of Paris in June 1940 put an end to their walks and coffee house encounters, and after 18 years of friendship, they never met again.

Of the war years, Serouya wrote: “(Soutine) trapped like a wild beast had to hide himself, always on the move, always in danger. When he came to Paris the demon of fear never left him. One sees the feverish state of mind in which he found himself, especially with his fervent imagination. The culmination of all the annoyances was the yellow star, a terrible reminder of medieval times. In 1940, before the German occupation, during my military service in the (French) army, Soutine showed me an engraving of a Polish Jew with a yellow star pinned to his back. Who would have dared to think that such a humiliation could reappear in the 20th century, and in the heart of Paris, the city of spiritual refinement?”

Following the German invasion, the La Ruche community broke up. French Jews including many of the artists went into hiding, and Soutine and Serouya both explored the possibility of emigrating to America. Serouya wrote: “It was only (later) that I learned by chance of the death of my dear friend. His death was not noticed, there was no mention in the newspapers, little arousal in the artistic community, not even a hushed whisper in the ears of the passersby. The death of Soutine, aged 49, at the height of his artistry, was a cruel loss to mankind.”

When he died in August 1943, Soutine was living with Marie-Berthe (MB) Aurenche, a painter, formerly married to the painter Max Ernst. They had met at the Café du Dôme in 1940 and soon became intimate. MB wrote about their three years together. Following the German invasion, they left Paris and went into hiding in Champigny, in Touraine, moving six times to new quarters. MB looked after Soutine during his final illness and was with him at the hospital where he died after an operation for a perforated stomach ulcer. It was she who made the funeral arrangements in the Montparnasse cemetery and prepared his grave in the burial plot which belonged to her family. Because of the Nazi occupation, it was not possible to have a Jewish burial ceremony or a Hebrew inscription on the tombstone. Thus Soutine was laid to rest under the sign of the cross – beneath a plain marble slab with neither name nor date. MB sold paintings by Soutine to pay for the funeral and the tombstone.

Serouya wrote a formal letter of condolences to Marie-Berthe. “Madame, I heard only yesterday evening the terrible news of the death of Soutine. He was my close friend, and the greatest painter of our generation. A year older than I, we were at one time inseparable. When I was demobilized in 1940, I went to see him at his home at 18 Villa Seurat. He told me he was planning to leave for America. This was the last time I saw him... Perhaps you will permit me to ask if I could see you next week, to hear from you something about his sad ending.” Marie-Berthe responded immediately: “Come today, around six o’clock, we will be able to have a moment together. Come and fetch me, at no. 15 of this street. I will be happy to meet a friend of Soutine’s... Believe me, in friendship, MB.”

Their meeting in September 1943 was the beginning of an intense relationship between Serouya and MB, a stormy affair that developed rapidly but lasted barely two years. Alongside these first polite formal messages (“cher monsieur,” “chère madame” neatly penned on official postal “cartes pneumatiques”) I found more letters in the brown suitcase, those from MB roughly scribbled in pencil on scraps of flimsy paper, enclosed in an envelope without stamp or address; perhaps they were simply left on the table, or pushed under the door. They were an ill-matched couple. MB, divorced, her lover dead, a beautiful woman of easy virtue, described as eccentric and unstable, needed someone to take care of her, to share her life. MB’s letters to Serouya are filled with declarations of love, apologies for the quarrels of yesterday's queries about his health, and complaints about his lack of understanding for her frequent absences and visits to friends. Serouya, a middle-aged bachelor, naïve and innocent where women were concerned, had fallen deeply in love with MB, but was fully aware of her faults and her instability. His letters to her bewail her canceled visits and her “unfaithfulness.” He criticizes and disapproves of her friends, male and female, who – in his words – were trying to keep them apart. He suffers, suffers, suffers (the word is repeated in every letter) – suffering from her behavior and from his own poor health, sleepless nights and bad dreams.

HIS DIARY entries are devoted mainly to his unhappy relationship with MB. To the diary, Serouya pours out his heart, his distress, his anger, his inability to reach a decision. On June 12, 1945, she left him, seemingly with another man. The entry for July 20 reads: “This morning I woke up in a state of rage. The memory of her treachery came back to me. I have an inexpressible hatred towards both of them. The tender feelings that I have for her are in direct contradiction to common sense and good reason. I suffer in her absence.” The August 15 entry reads: “The World War ends, Japan has capitulated.” Some thoughts follow on Hiroshima and the atomic bomb, on war and peace. Finally Serouya declares: “I believe, after an unexpected meeting with MB that I am about to be cured. I am trying to think less about her. But the problem of my life remains unresolved. It is very sad.”

There are only two entries for September: “I think about her from time to time, and my life, which is not happy.” Here his diary ends.

The war was over, Soutine was gone, MB and Serouya had separated. MB had become very disturbed and depressed. Serouya returned to his desk, to write about Judaica and philosophy, and about his friend Soutine. In a letter to MB he tells her: “My article (on Soutine) has aroused much interest. Prices for his works have risen… Your name appears in America.”

MB responds: “After our recent conversation I forbid you to use my memories for the book you are writing about Soutine, or to mention my name in either your book or in your articles… No, no, no! I hope you understand.” In his manuscript drafts Serouya indeed takes note of MB’s demand and deletes her name. She goes on to warn him against Madeleine Castaing, Soutine’s wealthy patron and collector of his works, who she claims is trying to influence Serouya in his writings about Soutine. “Serouya, beware of la mère Castaing.” She writes, “With her flatteries she will use you to write the book she wants; a) because you know Soutine; b) because you are poor; c) because you are a good writer.”

In the years that followed her divorce from Max Ernst, MB faced legal issues concerning the settlement and became ever more unstable. After two attempts to commit suicide, MB took her own life in 1960. In compliance with her request, she was buried in the same grave as Soutine, where space had been left for her.

Serouya was unable to accept that his friend had not been given a Jewish burial. In 1963 the French Jewish magazine L’Arche reported: “For nearly 20 years the painter Soutine has been lying under the shadow of a cross. His remains were protected by a false certificate of baptism. Soutine’s grave was recently discovered by the philosopher Henri Serouya, a friend and companion of the artist during the years of occupation. Nevertheless much official research was needed, together with a due request from family members in Israel, for Soutine to be restored to his Jewish origins.”

Serouya arranged to have a square of marble inscribed with Soutine’s name and the Star of David. This was attached to the tombstone bearing the cross and MB’s name.

He also informed Soutine’s family. After the exhumation and reburial ceremony, Serouya wrote: “I was overcome with emotion when the coffin was raised. Soutine was there, forever enclosed in a box… My old friend is no more. I could see him again – his back somewhat rounded, his lovely hands, his abundant black locks, combed with loving care. Never again would Soutine stroll the picturesque streets of Montparnasse, a Gauloise cigarette between his lips… He loved the quarter, cradle of his early misery and later of his fame… When the German occupation ended, I thought how happy Soutine would have been at the liberation of the city which he so loved.” Soutine wrote little about himself, leaving no letters or diaries for the art historian or biographer to pore over. Serouya was conscious of the lack of documentation, and in 1954 wrote a full-length biography of the painter. This was never published. In the brown suitcase, I found the manuscript, together with several letters of refusal from publishers, American and French. Serouya’s financial situation in the 1960s had deteriorated, and he needed money. In the brown suitcase are receipts indicating that he had found a buyer for 98 letters, signed by distinguished public figures – the Chief Rabbi of France, Israel’s Ambassador to France, Max Nordau, various artists including Chagall, and a large packet from Soutine. Interest in Soutine had risen in the years following his death, likewise the prices paid for his paintings. Authors thinking of writing a biography of the painter hoped Serouya’s trove of letters sold by an auction house in America would throw light on the reclusive artist. But it turned out that these letters were mostly messages relating to social events. Why Serouya did not find a publisher for the biography is not clear. In 1967 the French firm Hachette published Serouya’s book on Soutine in their series Master Works of the Great Painters, in a large format with 16 excellent illustrations. Serouya insisted on high quality paper and fine colour reproduction. But Serouya’s text – a few pages of introduction and a brief survey of Soutine’s life and works lifted from the unpublished biography – is meager. Serouya must have been disappointed.

So what happened to the unpublished manuscript? Well, it’s still in the brown suitcase, some pages missing, and is now on my desk, with all the other documents, typed, published, and handwritten, that prompted this article.

UNCLE HENRI kept every scrap of paper he received and made copies of every letter he sent. He clearly regarded them as belonging to a Serouya archive. After his death his papers were sent to the family in Jerusalem. His own library had been impounded by the Nazis. I talked to family members and to people who know about archives, and we set up an ad hoc committee. We contacted the library of the Alliance Israelite Universelle in Paris and learned that they already possess a Serouya archive and would be happy to combine it with ours. There were those who thought the material should remain in Israel, but little interest was shown by the National Library in Jerusalem. The AIU is an important international organization founded in 1860 to promote French-language education for Jewish children. Uncle Henri, who died in 1968, had studied at the Alliance school in Jerusalem, as did other members of the Serouya family including his nephew Joseph, and his great-niece Zipporah Vadislavsky who as a committee member has contributed much family history. So the vote went for Alliance and the documents are being dispatched to Paris.

In recent years there have been major Soutine exhibitions in the US, Europe, the UK, and Israel. In 2020, the Mishkan Museum at Kibbutz Ein Harod presented a fine Soutine exhibition with 18 of his paintings from museums and private collections on display.

In Paris, the Museum of Jewish Art and History recently mounted a fine exhibition of works by Chagall, Modigliani, and Soutine accompanied by a splendid catalog.

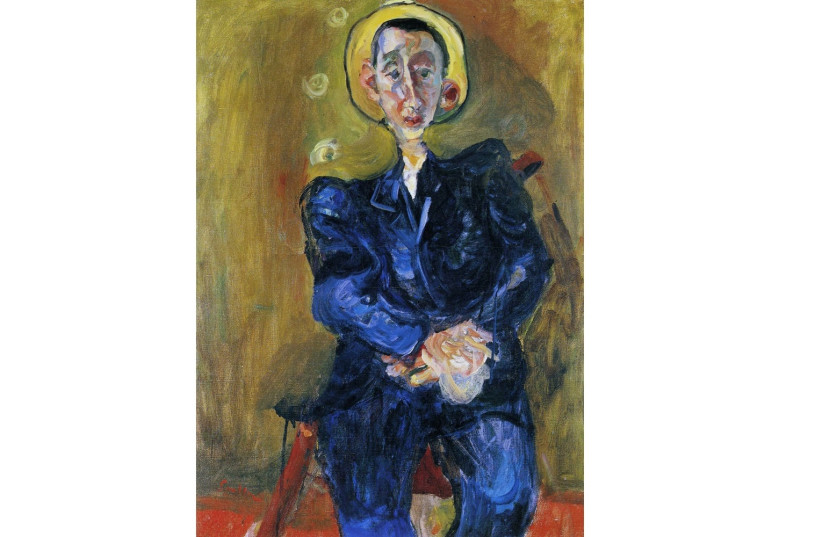

A FINAL NOTE: many years ago I came across the catalogue of a Soutine exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, London 1982. I was struck by a picture titled Man in a Blue Suit.

I looked again and said: “I see a resemblance to Uncle Henri.”

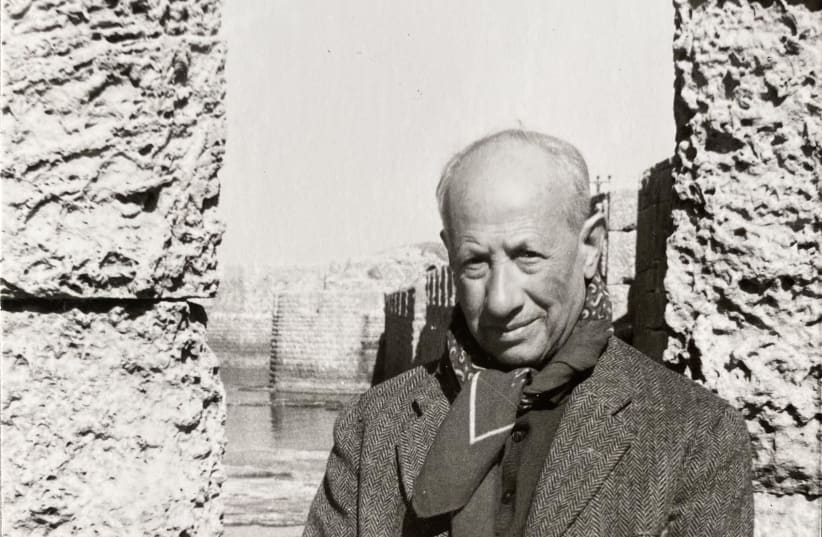

Here are two photos of Uncle Henri, one dated Cairo 1924, the other Israel 1961, together with Soutine’s Man in a Blue Suit dated 1924.

Could it be? I knew of the friendship between the two men but there was no one to ask. Now with the brown suitcase in my hands I have been hoping to find a mention that Soutine had painted Serouya’s portrait. So far nothing. The experts agree with me that there is a likeness, but say that only clear documentation in writing would serve as confirming evidence. If you can make a connection – let me know. Sara Manobla <manoblasara@gmail.com>