“Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu appeared in a Jerusalem courtroom Monday to respond formally to corruption charges just weeks before national elections in which he hopes to extend his 12-year rule,” read the lead paragraph to a matter-of-fact AP news story.

People around the world, reading that article, might very well think to themselves, “Wow, Netanyahu is appearing as a defendant in a corruption trial just weeks before an election? Surely this will hurt him.”

But those people would be wrong.

The AP reporter was right to link the two events – the trial and the elections – in his story’s opening paragraph. The corruption trial of a prime minister would, under normal circumstances, surely impact on his chances in an upcoming election.

But these are abnormal circumstances, and Netanyahu’s appearance in court on Monday will likely have little impact on how people will vote on March 23.

Why not? Because this saga has been dragging on for almost five years; because the country’s citizens have pretty much made up their minds about what they think about the charges; because three elections have already been held in the shadow of the indictments and did not lead to Netanyahu’s downfall.

In fact, of those three elections, Netanyahu’s Likud Party garnered the most votes and Knesset seats in two of them and only slightly slid behind the Blue and White Party in the second (September 2019).

That the Likud won the most votes in the first election in April 2019 and again in the last one in March 2020 shows the limited impact the corruption charges have on Netanyahu’s base.

The April 2019 election came less than two months after Attorney-General Avichai Mandelblit announced his intention to indict the prime minister on charges of bribery, fraud and breach of trust, pending a hearing, stemming from three different cases. And the March 2020 election – when Likud won 36 seats, more seats than the party has won any time since 2003 – came less than two months after Netanyahu was formally indicted and headlines in the media read: “The State of Israel vs Benjamin Netanyahu.”

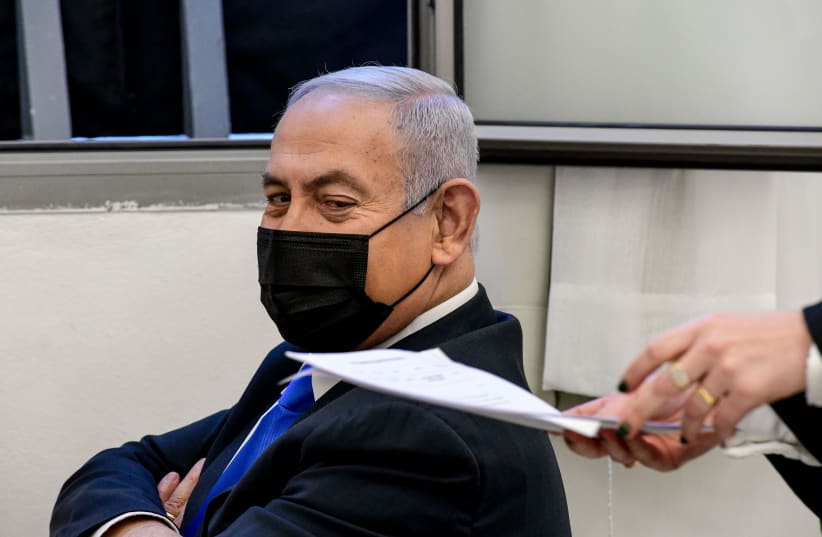

This time, some may argue, it is different, because this time the trial has actually started, and there are pictures and drawings of the prime minister in court.

But while visuals of the prime minister in court in the midst of a campaign are obviously not ones any campaign strategist would want for his candidate, if the past is any prediction, that the trial has started will unlikely have an impact on Netanyahu’s core of support.

Those who support Netanyahu support him and are unlikely to be swayed by preliminary steps in court, and those who believe he is corrupt were not waiting for this moment to validate their opinions.

The fault lines on Netanyahu were drawn long ago, and the proceedings in the Jerusalem District Court are unlikely to move anyone from the pro-Bibi camp into the anti-Bibi camp, or vice versa. It is not as if a pro-Netanyahu supporter in Tiberias is, as a result of seeing the prime minister in court, going to wake up in the morning, bang palm to forehead, and say, “What a crook.”

Preliminary investigations into the three cases involving Netanyahu before the courts began in the summer of 2016, almost five years ago.

Since then, the country has been flooded with news and leaks about the cases, as well as with counterclaims by Netanyahu and his supporters that there is nothing to the charges, and that they are little more than the Left trying to bring down a right-wing prime minister through the courts since they can’t do it at the ballot box.

This particular argument has gained credence among Netanyahu backers because of a clumsiness in which Mandelblit and the state prosecutor have conducted themselves in investigating and prosecuting these cases, as well as in other cases – like the convoluted Harpaz Affair – in which they were involved.

When the public hears tapes of Mandelblit saying that the state prosecutor has him “by the throat,” or reads excerpts from emails showing that the Justice Ministry’s Police Investigation Department did not follow up on an insider complaint against methods the police used to get a former Netanyahu confidant to turn state’s witness, that all buttresses Netanyahu’s allegation among his supporters that the Left and the judicial system are out to get him.

Another reason that the cases against Netanyahu have not shaken his core of support is because to many, his alleged crimes are not seen as that egregious.

Bribery, in the public mind, is associated with dollars changing hands in paper bags, not – as in Case 4000 – giving favors from the Communications Ministry to the owner of a media outlet in order to get favorable coverage. As to the allegations of gift taking, many view this as behavior not beyond the norm.

And even if gifts were given to Netanyahu, his hard-core supporters argue, even if he did take champagne and cigars and went overboard in trying to secure good press, that’s no reason to bring down a leader of world stature who has brought Israel to unprecedented economic, strategic and diplomatic heights. These supporters, obviously, will not be swayed by Netanyahu’s appearance in court.

In the five years since the first case (Case 1000) broke, most people in the country have made up their minds regarding whether they believe the prime minister took advantage of his offices for personal gain, or whether the police and the legal establishment are out to get him. Five years is plenty of time to make up one’s mind.

Netanyahu’s political rivals also understand this, which is why none of them – with the exception of Blue and White’s Benny Gantz – tried to gain political capital out of Monday’s court appearance.

While Gantz put out a much-worn statement that the appearance of a prime minister in court is both a sad day because of what it means, and a proud one because it shows no one is above the law, Netanyahu’s other main political rivals – Yesh Atid’s Yair Lapid, New Hope’s Gideon Sa’ar, Yamina’s Naftali Bennett and Yisrael Beytenu’s Avigdor Liberman – posted no statements on social media blasting Netanyahu for bringing the country to this moment.

It is as if they realize there is little to gain by harping on an issue that has received so much exposure for so long, and that to concentrate on Netanyahu’s alleged malfeasance – which not everyone believes – would detract attention from the government’s malfeasance that everyone is feeling and which they want to underline: It’s dealing with the coronavirus.