Two exceptionally well-made and fascinating new documentaries about two legendary Israeli literary figures – Amos Oz and A. B. Yehoshua – were made by one filmmaker, Yair Qedar.

The Fourth Window, a documentary about Oz, was recently shown on Kan 11 and is currently available on the network’s website, and the A. B. Yehosuha documentary, The Last Chapter of A. B. Yehoshua, which had its premiere at the Jerusalem Film Festival, will be broadcast on Kan on October 6 and will subsequently be on its site.

Qedar, who has made a number of acclaimed films, including several previous documentaries about poets and writers, among them Black Honey, the Life and Poetry of Avraham Sutskever, admitted in a recent interview that it was a bit daunting – and very labor-intensive – to do justice to these literary giants. “It’s like you do a doctorate on each one,” he said.

“In the past I have done films about writers of an older generation, decades after their death and you know how their work is regarded. But when you are doing a documentary about a living artist, or a recently deceased one, you can’t know how their work will hold up,” said the director.

Qedar – who studied literature, not film – decided to focus on the intersections between their lives and work. “Oz and Yehoshua are Israelis whose work went around the world, they are the first generation of Israeli writers where that happened. I gradually got interested in writers’ lives... I wanted to get at what was behind each writer, how each writer’s life was connected to his work.”

Qedar has succeeded in this quest in both of the films. The writers’ lives are used to illuminate what drove them to become writers and he shows how their childhoods and backgrounds shaped them and enriched their work. You leave both of these entertaining and lively films with a feeling that you want to revisit their work. More than that, once you read or think about their books again after seeing these films, you will feel that you know them better and appreciate them more, which is exactly what Qedar set out to do.

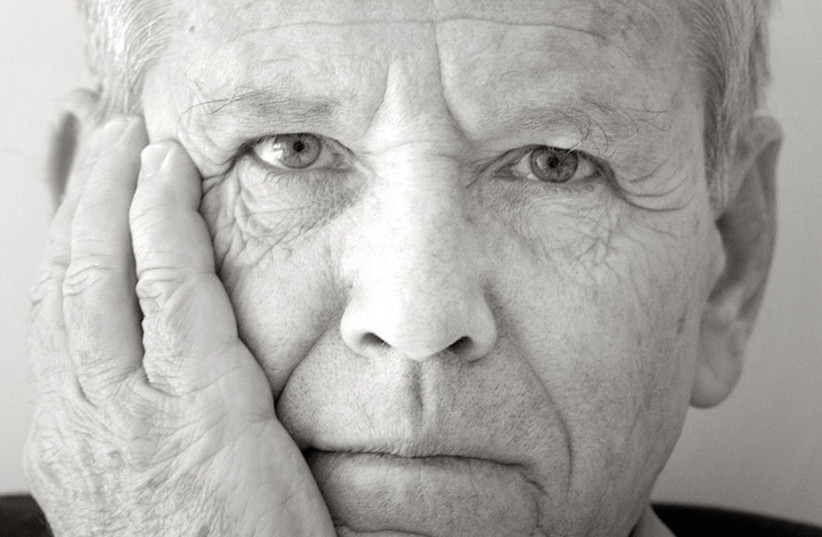

THE OZ documentary, which is organized around intimate conversations that Oz had with his biographer and friend, Nurit Gertz, a couple of years before he died in 2018, shows how his life was bookended by two tragedies. The first was the turmoil in his family during his childhood, caused by the mental illness of his mother, whom he loved very much. After several tough years, she committed suicide, which he wrote about so memorably in A Tale of Love and Darkness but which also informed many of his works, notably My Michael.

The film also discusses the fact that he felt abandoned when his father remarried and went abroad not long after his mother’s death and details how his choice to move to a kibbutz was a rebellion against his father, a librarian, who was not thrilled that his son was driving a tractor. While the story of Oz’s mother is widely known, Qedar tells it movingly and also explains how, in many ways, he became a writer out of his struggle to deal with it.

“I realized that the pain of the loss of his mother was something he could never completely express, even in A Tale of Love and Darkness... Oz was an orphan, he had lost both his mother and his father. He had to completely reinvent himself and he did,” said Qedar.

The second and much later tragedy is the rift with his daughter, Galia Oz. Galia published a memoir this year, Something Disguised as Love, where she alleged that her father abused her physically and emotionally on a regular basis while she was growing up.

“I had just finished the film and then the news about Galia’s book came out,” he said. “It was a difficult film to make and then I had to start again.” None of the family wanted to speak about it to him and “it was a delicate dance, I didn’t want to push too hard.” Qedar presents conversations between Oz and Gertz about Galia, which are very revealing. It turns out that long before the book was published, she had spoken to her family about the abuse and in several conversations with Gertz, Oz tries to figure out how he can repair their relationship. He does not dispute everything she alleges, and acknowledges his shortcomings as a father, trying to figure out a way to reconcile with her. That reconciliation did not come and he seems to have spent his last years haunted by this failure.

“You see how it caused him pain, how he thought about it,” he said. Qedar does not take sides and this section, which does not dominate the documentary but which is an important part of it, adds layers of complexity to its portrait of Oz.

ALTHOUGH YEHOSHUA is alive – he was interviewed extensively for the film and attended the Jerusalem Film Festival screening, where he gave a brief speech – in many ways, his story is more elusive than Oz’s. Yehoshua, whose friends call him Buli, is a man of many contradictions. These are present in his novels and stories, which resist categorization but which have won acclaim both at home and abroad. Following the death of his beloved wife, about whom he speaks with great affection in the film, he left Haifa, where he lived for decades and where some of his books were set, and took up residence in a high-rise in the Tel Aviv area.

The movie is both a biography of the writer and a look at where he is now, as he protests that he does not want to write anymore – but he keeps writing, and just published a new novel, The Tunnel, in 2020 – and that he is ready, after struggling with health issues in recent years, to say goodbye to life. But as friends visit him – much of the movie was filmed during the pandemic and a great deal of it is set in his home – and he goes out to give readings and to meet with politicians and intellectuals in Ramallah to discuss politics, he seems engaged by the world.

Born in Jerusalem (where his acquaintances included Oz and former president Reuven Rivlin), with a father who was a scholar and historian, fluent in Arabic, and a Moroccan-born mother who was also very engaged with culture, Yehoshua was exposed to an unusually wide range of influences at home. However, all his life he resisted being labeled as a spokesperson for Mizrahi Jews, despite the fact that many of his characters are immersed in their Mizrahi heritage. He tells a funny anecdote in the film about how his mother – being interviewed at a residence for seniors – was reluctant to admit she was born in Morocco.

“Compared to Oz, he had a more grounded family, he absorbed a lot of culture from his family, including Arab culture,” said Qedar. “He refused to be pegged as a Mizrahi writer, he fought against it, he did not want to be ghettoized and he is constantly surprising you, his books don’t follow a conventional narrative and they are not about Mizrahi oppression. When he wanted to deal with Eastern-ness he did it in a roundabout way, in Molcho [known in English as Five Seasons], about a man who loses his Ashkenazi wife, decades before this happened to him, and Journey to the End of the Millennium, which is set over a thousand years ago.”

His political activism has been unusual as well. He has criticized Israeli policies and pushed for a one-state solution. At the premiere of the documentary, at which Rivlin was present, Yehoshua addressed him directly during his speech, asking when he would push to offer citizenship to Palestinians. He did not seem to be surprised when the former president, who had left office just a few weeks before, did not answer.

In spite of his many statements and writings about politics, however, it seems that one of his early stories, “Facing the Forests,” a provocative tale of an army reservist guarding a forest that was planted over the ruins of an Arab village with an elderly Arab whose tongue has been cut out in the War of Independence, has had more influence on politics than any article he has written. Discussing the story with a group of high-school students, Yehoshua lights up as a younger generation engages with his work.