The world’s climate is changing – again. But instead of getting warmer the last time like it is now, in around 6,200 BCE, it was getting colder.

A drought resulted and launched what was called the 8.2ka (kiloyears – thousands of years – ago), which began about 8,200 years ago and lasted for the next two to four centuries in the southern Levant that includes modern-day Israel, the Palestinian territories, Jordan, Lebanon, southern Syria and the Sinai desert.

Until now, archaeologists thought that this sudden cooling in global climate led to the widespread abandonment of coastal settlements in the southern Levant. However, researchers at the University of Haifa, Bar-Ilan University (BIU) in Ramat Gan, and the University of California at San Diego have produced new evidence suggesting that at least one village formerly thought abandoned not only remained occupied but thrived throughout this period. They said the study helped fill a gap in our understanding of the early settlement of the Eastern Mediterranean coastline.

They have just published their study in the journal Antiquity under the title “Continuity and climate change: the Neolithic coastal settlement of Habonim North, Israel.”

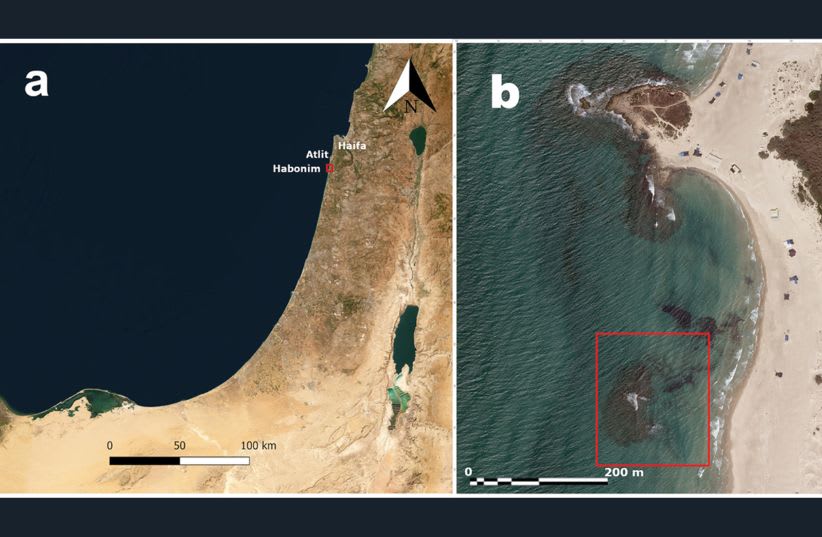

The village of Habonim North was discovered off the Carmel Coast in the mid-2010s and later surveyed by a team led by the University of Haifa’s Dr. Ehud Arkin Shalev. The study was led by Prof. Assaf Yasur-Landau, head of the Leon Recanati Institute for Maritime Studies at the University of Haifa, and Roey Nickelsberg, a doctoral candidate there. BIU Prof. Ehud Weiss and Dr. Suembikya Frumin also participated.

“This study helped fill a gap in our understanding of the early settlement of the Eastern Mediterranean coastline,” said Prof. Thomas Levy, a co-author on the paper, co-director of UC San Diego’s Center for Cyber-Archaeology and Sustainability (CCAS) and chairman of Archaeology of Ancient Israel and Neighboring Lands in the anthropology department of the university’s graduate division.

Unearthing the Levantine coastline

“It deals with human resilience,” he said. An experienced scuba diver, Levy spent 40 years carrying out archaeological field work in the deserts of Israel and Jordan.

Before its excavation and analysis, there was little evidence for human habitation along the southern Levantine coast during the 8.2ka event. The dig, which involved a weeks-long, 24/7 coordinated effort between the partners in the two countries, was the first formal excavation of the submerged site.

Animal bones

LED BY Yasur-Landau and Nickelsberg, the international team excavated the site using a combination of sediment dredging and sampling, as well as photogrammetry and 3D modeling. Team members uncovered pottery shards or “sherds”; stone tools, including ceremonial weapons and fishing-net weights; animal and plant remains; and architecture.

Using radiocarbon dating, the researchers tested the recovered bones of wild and domesticated animals, the charred seeds of wild plants, crops like wheat and lentils, and weeds that tend to accompany these crops. Their results traced these organic materials back to the Early Pottery Neolithic (EPN), which coincided with both the invention of pottery and the 8.2ka event.

Pottery sherds, stone tools and architecture in the village were also evidence of activity at the site to the EPN and, surprisingly, to the Late Pottery Neolithic, when the village was thought to have been abandoned.

As for how the village likely weathered the worst of the climate instability, the researchers point to signs of an economy that diversified from farming to include maritime culture and trade within a distinct cultural identity. Evidence includes fishing-net weights; tools made of basalt, a stone that does not naturally occur along this part of the eastern Mediterranean coast; and a ceremonial mace head.

“Our study showed that the Early Pottery Neolithic society displayed multi-layered resilience that enabled it to withstand the 8.2ka crisis,” noted Yasur-Landau, a senior author on the paper. “I was happily surprised by the richness of the finds, from pottery to organic remains.”

Although scientists debate the cause of the 8.2ka event, some speculate that it began with the final collapse of the Laurentide ice sheet, which shaped much of the North American landscape in its retreat from modern-day Canada and the northern US. As it melted, the ice sheet would have changed the flow of ocean currents and affected heat transport, leading to the observed drop in global temperatures.

Many of the activities uncovered at the village, including the creation of culturally distinct pottery and trade, formed the basis for later urban societies. “To me, what’s important is to change how we look at things,” said Nickelsberg. “Many archaeologists like to look at the collapse of civilizations. Maybe it’s time to start looking at the development of human culture, rather than its destruction and abandonment.