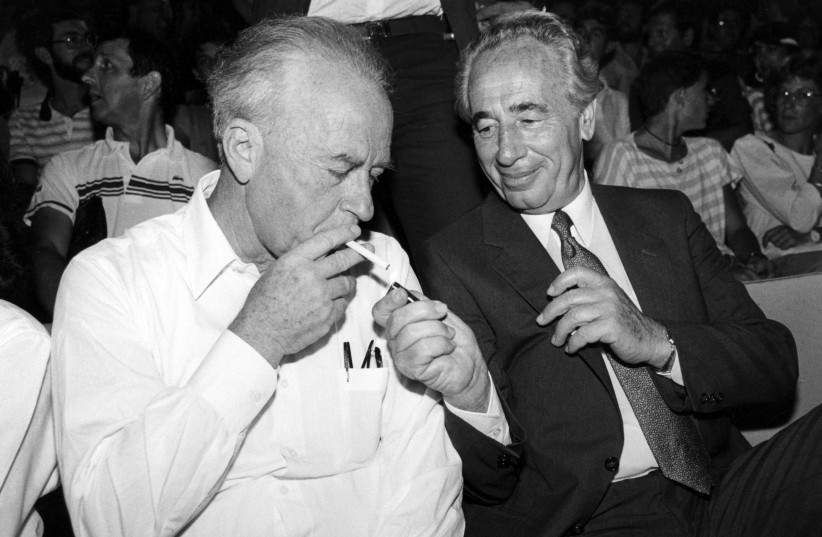

As the Israeli government discussed the first of the two Oslo Accords in 1993, then prime minister Yitzhak Rabin admitted that he believed a basic condition of the agreement, Palestinian elections, was unlikely to actually happen, according to the protocol of a cabinet meeting which was declassified on Tuesday.

The cabinet meeting took place on August 30, 1993, about two weeks before the Oslo I Accord (the first of the two agreements making up the Oslo Accords) was signed between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in Washington DC.

The Oslo I Accord, also called the Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements, provided for the establishment of an interim Palestinian government which would eventually lead to a permanent peace agreement. The agreement would be in effect for a transitional period of at most five years.

The agreement stated that free and general elections would have to be held in order to establish a council that would govern Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. The council would be given jurisdiction over education, health, social welfare, taxation, and tourism in those areas. Any further issues would be handled in a future agreement.

Rabin told the cabinet that he believed that the chances of Palestinian elections being held and the council actually being formed were "small."

"It is no coincidence - and I think, quite wisely - that the five-year clock starts ticking from the signing of the declaration of principles and not after the elections, so as not to hasten the matter of the elections." Rabin was later corrected that the five-year clock started from the moment Israel withdrew its jurisdiction from Gaza and Jericho, not from the moment of signing.

Rabin noted that the agreement could lead to positive and negative developments, and stressed that the agreement which would be signed would have "reversibility." The prime minister stressed as well that the declaration of principles wouldn't change the existing situation much, only giving some early forms of self-government for at least the first nine months.

"I want to emphasize, the jurisdiction is not automatically being given to them, it will only be given to the council. As long as there is no council, there is no jurisdiction."

Rabin expresses concern over rise of Hamas

Rabin told the cabinet that in his eyes, the first test of the Accords would be if the PLO could control Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

Rabin additionally noted that "the rise of Hamas in particular and radical Islam in general in the Arab world is a problem. I think we are seeing this rise among the Palestinians as well. I believe that, in most of the elections in the territories today, Hamas is rising."

When asked if there was an assessment of what would happen in the elections for the Palestinian National Council, Rabin responded "I have no way of knowing, because the problem is who will threaten more, who will be with guns near the polling stations, and who will count the votes."

"Basically, for me, Gaza is a case test for the ability of those who support peace and support the PLO to deal with Hamas. Will it go in this direction or in other directions - I estimate, it mainly in this direction, but there is no certainty. There is a good chance," said Rabin. "But the IDF exists. There is a closure on Gaza from all directions, no one can enter or leave without our consent, not from the sea, not from the Egyptian border, not from the territory of Israel."

The prime minister admitted that the main worrying point of the deal is that it included a lot of commitments from the Israeli side, but very few commitments from the Palestinian side. Rabin added that the Palestinians were formulating some kind of statement that they would stop violent actions, but added that the exact formulation remained unclear.

Then foreign minister Shimon Peres stressed that the deal needed to succeed both politically and economically and explained that he and Rabin had asked European and American institutions to begin heavily investing in Palestinians in the territories.

Peres warned, "there is a possibility that the whole PLO business will fall apart and there will be a kind of Hamas-like Iran here."

"We also need to be careful. There is no certainty that they will last, with all the rebellions, with all the begging, with all the pressures and all the things that exist. I say this is a very serious matter. I simply do not see an alternative in the Arab street, with all the shortcomings there are, that is better than the current coalition that exists."

Peres stressed that the Israeli negotiating team had not given up an inch of territory. "We did not remove a single settlement, we preserved the unity of Jerusalem, we ensured Israel's security."

Deri: I do not think the Palestinians pose a security danger to the State of Israel

Then interior minister Arye Deri stressed that the spiritual leader of the Shas party, Rabbi Obadia Yosef, saw the matter of peace as "quite central." Deri stressed, however, that the government would need to figure out how the deal would actually help Israel's national security.

"I agree with you that the Palestinian problem is a very difficult political problem, but I did not understand why it poses a security danger to the State of Israel. A security danger is Syria and not the Palestinian state. Perhaps because of the stipulation of the Arab countries regarding the Palestinians, this is a security danger, but if this stipulation does not exist, I do not think that the Palestinians pose a security danger to the State of Israel."

Deri additionally noted that the government would need to take care not to cast those living in the settlements as a security burden to the state and would need to ensure that they could protect their lives.

The former interior minister questioned, "aren't we putting over 100,000 Jews, or more, into a state in which their lives are at risk?"

"The chief of staff and other ministers did not deny the fact that today we do not know how to answer the safety of these Jews. I am sure that the IDF and the police will do everything to ensure this, but the questions remain open," added Deri. "Those people who live in the West Bank today want answers. Apart from the emotional problem of giving up territory, there is an existential problem - what are we doing for the children who travel to school? There are no answers. I don't think it's serious to come and tell them - we promise you full security."

Deri called for the government to work hard to convince the public that the deal was a good one.

"You know that peace is not made only between two sides, the people must also be with you. When the public thinks that this is a victory for the Meretz and the justification of its political path to this day, then maybe the members of the Meretz are really satisfied because they think that their leadership led to this thing, but a part of the public which is just as important, that you want to be a partner in this move, you are alienating him in actuality."

"Psychologically, the public has not digested that they are going to a peace process. In the meantime, there are only our concessions, and the right takes advantage of this in a very strong way." "There must not be a situation, God forbid, where it will be seen that the government, due to pressure, accepted this path. Therefore, for the benefit of the subject you believe in, you need to go for consensus."

"It is not a shame to say - we went and implemented [former prime minister Menachem] Begin's Camp David agreement. It is not a shame to say that we will protect the safety of the citizens. Despite the differences of opinion, they are first-rate citizens and we will protect them and not abandon them. This is not a permanent arrangement, it is not an introduction to a Palestinian state."

Deri added that in light of all the concerns surrounding the deal, he could not vote in favor.

Israel and the Scandinavians

During the cabinet meeting, Peres also referenced the relations between Israel and the Scandinavian nations, noting that the relations had suffered under the previous Likud government. The foreign minister recounted how Finnish citizens had expressed outrage when there were reports that Israel intended to appoint an Arab as ambassador to the country.

"Non-Jews, gentiles, contacted me and said: 'In the name of God, what are you doing to us? We support the Bible, we support the chosen people, and you're sending us an Arab?' All those Gentiles who support the Arabs, when they heard that Israel wanted to send an Arab ambassador, were shocked...This is not a matter of racism, but a religious matter."