Israelis, as well as Americans and others who have carefully followed the news – especially in the past year – have become especially knowledgeable in misstatements – falsehoods or out-and-out lies – intentionally voiced by their political and other leaders.

In a new study, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University (Pittsburgh), Rice University (Houston), the University of Colorado-Boulder, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology used online surveys conducted primarily when Donald Trump was president to show that both Republican and Democratic voters provided explicit moral justification for politicians’ statements that were factually inaccurate, especially when they aligned with their personal politics.

Just published in the American Journal of Sociology under the title “When Truth Trumps Facts: Studies on Partisan Moral Flexibility in American Politics, the study found that political misinformation isn’t just about whether voters can tell facts from fiction,” said Prof. Oliver Hahl, an expert in organization theory, strategy, and entrepreneurship at Carnegie Mellon’s Tepper School of Business, who coauthored the study. “It seems like it’s more about how statements – whether true or not – speak to a broader political agenda.”

The prevalence of confirmation bias

Importantly, results from the last two surveys indicated significant moral flexibility among both Democrats and Republicans.

Researchers conducted six surveys to assess voters’ responses to statements by politicians that flouted the norm of fact-grounding – that one should stick to facts when giving a statement – while proclaiming deeper, socially divisive “truths.”

Five were conducted during Trump’s presidency, and one was conducted in the spring of 2023. Participants were recruited from either Amazon’s Cloud Research Platform, a crowd-sourcing platform that assists people with virtual tasks, or Prolific, a research platform that provides academics and companies access to participants for studies and surveys.

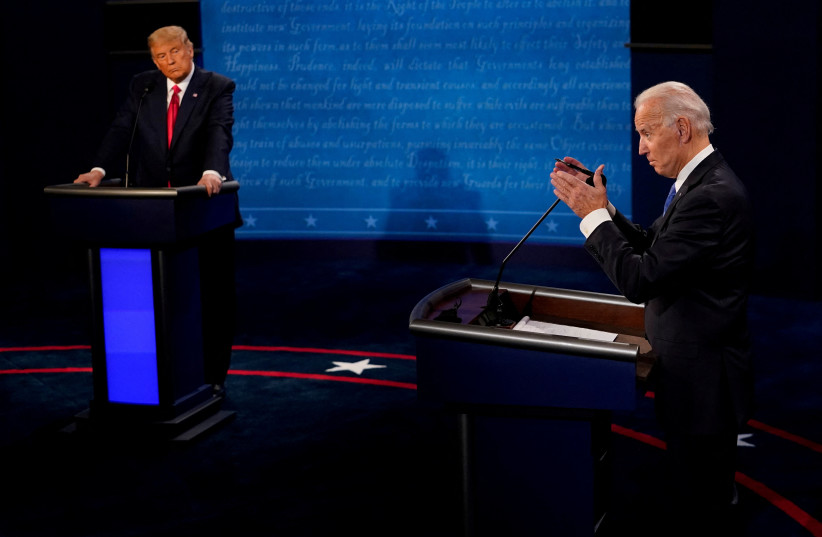

All six surveys had similar structures and questions, though some questions were specific to a particular political context. Each survey gauged voters’ reactions to false statements by politicians, including Trump, Florida’s Governor Ron DeSantis, US President Joe Biden, and New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

The results of all the surveys showed a significant tendency by politicians’ supporters to deliberately favor violations of the norm of fact-grounding, justifying these factually inaccurate statements in moral terms when they could have relied on a factual justification. The surveys also provided consistent evidence that voters distinguish between objective evidence and truth, favoring the latter when judging statements of favored politicians and the former when judging disfavored candidates.

The results challenge the common belief that partisan voters’ positive reactions to misinformation from their party leaders result solely from laziness or bias – leading them to confuse factually inaccurate information for truth. Instead, the evidence consistently shows that voters are flexible with the facts – exhibiting factual flexibility.

However, they also provide consistent evidence of moral flexibility in which voters justify demagogic flouting of facts or disregarding or ignoring facts, as an effective way of proclaiming a deeply resonant political “truth.” A key implication is that political misinformation can’t be eliminated by getting voters to distinguish fact from fiction; voters’ moral orientations may be such that they prefer fact-flouting.

In most studies, Trump supporters showed considerable “flexibility” with the facts regarding his statements. However, the study focusing on the “big lie,” which surveyed only those who voted for Trump in 2016, proved to be an exception.

Conducted in 2021, the survey explored voters’ responses to Trump’s claims that the 2020 US presidential election was “rigged” or “stolen.” Participants were more likely to consider Trump’s allegations as grounded in objective evidence rather than subjective viewpoints.

Compared to other topics, Trump’s allegations that the election was stolen were portrayed as factual. There is less moral flexibility with this issue, possibly because these claims were presented more as facts. However, the emphasis on factual accuracy concerning the big lie still varied based on people’s political affiliations.

Among the limitations of their work, the authors note that the statements used in the surveys represented just one type of political misinformation (demagogic fact-flouting by partisan politicians). In addition, the measurement and analysis strategy used was new and lacked a track record, and the samples were not nationally representative.

“Our findings reiterate the sociological insight that commitment to democratic norms cannot be assumed and indicate the importance of that caution when it comes to the problem of political misinformation,” said management Prof. Minjae Kim at Rice University’s Graduate School of Business who was a study coauthor. “In particular, efforts to combat voters’ positive response to misinformation cannot be limited to teaching them to simply work harder to digest accurate information by fact-checking.”