The bad news is that COVID-19 is here to stay. The good news is that this will eventually be stabilized – it just has not happened yet.

Pandemics do not have a start or an end date.

“We have this expectation that COVID-19 had a start: It started in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. And we have this expectation that it is going to end,” said Dr. Daniel Landsberger, chief physician for Maccabi Health Services. “We want a date for it to end.”

But if we look over hundreds of years, pandemics are processes.

The Bubonic Plague of the 16th century lasted a few hundred years and there are still random but rare outbreaks today – mostly in Third-World countries like Africa, India and Peru.

The first reported cases of HIV were reported in the United States in 1981. A decade later, HIV was the No. 1 cause of death among Americans ages 25 to 44, according to WebMD. And it took until after 2000 before the latest class of HIV drugs emerged that allow people to live with and manage the disease.

“HIV has not ended,” Landsberger stressed. “We just don’t call it an epidemic anymore. We relate to it differently.”

He said that epidemics are not just “biological events,” but social, cultural and geopolitical events. So, while Israel might see the rate of infection decline or nearly disappear, as happened in the late spring, other countries might continue to be plagued by the virus.

This is even the case when there are viable vaccines, such as the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines that exist to repel the coronavirus.

More than 5.8 million Israelis are vaccinated.

Why, if there are such good vaccines, has the pandemic not ended?

To understand, one only has to look at the poliovirus vaccine that was invented in the 1950s. Distribution started in the US in 1955, but the last cases of polio were reported as late as in 1979.

“It took many, many years for polio to be eradicated from the US, despite having a vaccine that is 95% effective,” Landsberger said.

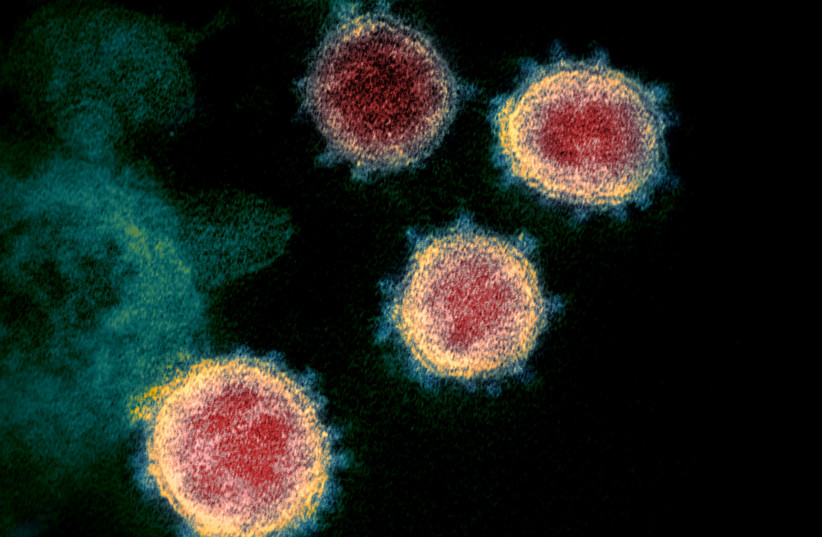

Also, as long as there is a virus, there will be virus variants.

On Monday, Dr. Asher Salmon, director of the Health Ministry’s Department of International Relations, told the Knesset that there was a South American variant that had made its way into the US, and if it came to Israel, “we will reach the lockdown that we so desperately want to avoid.”

FIRST, HOW a variant behaves in a country in South America does not necessarily reflect how it will behave in a country such as Israel. That’s because countries such as India or Peru have challenged health systems and high levels of poverty, explained Yasmin Maor, head of the Infectious Disease Unit at Wolfson Medical Center.

“It is difficult to extrapolate how a particular variant will behave with a better health system,” she said, recalling the South African variant that threatened to break the Israeli healthcare system but barely infected Israelis.

That’s likely one of the reasons that Health Ministry Director-General Nachman Ash said later Monday in an interview with KAN News, “I do not want to create unnecessary panic.”

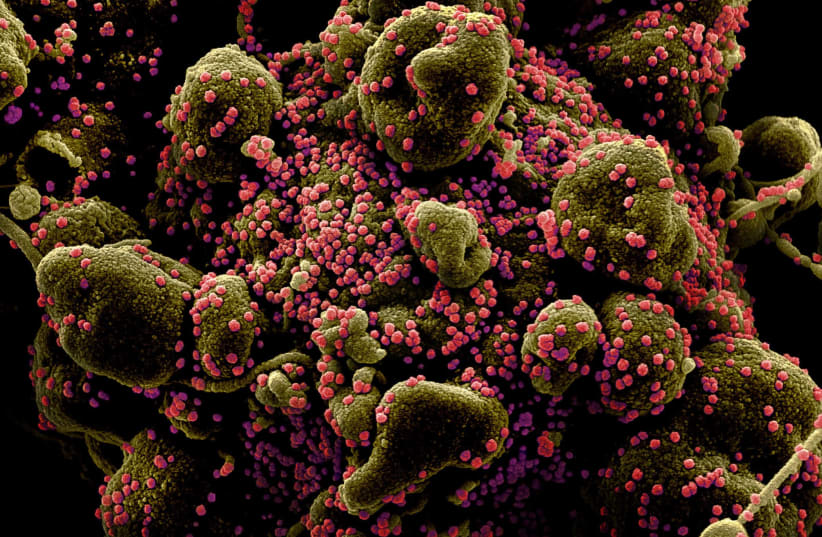

Viruses replicate and sometimes during replication they mutate or change. But viruses do not mutate in the air. Rather, they mutate inside their host – people. The more people are infected, the more variants there are going to be. Therefore, the way to reduce the number of variants is to reduce the number of people who get sick.

Health officials have said that the COVID virus does not mutate that often compared to other viruses – specifically compared to the flu virus. Nonetheless, any change in the nature of a virus can bring with it a set of challenges.

“The idea is that we are going to see more variants,” Maor said. Meaning, the bad news is that “neither the Delta nor the South American variant is the last one.”

The good news is that Israel has vaccines, and they work.

Between January 1, 2021, and August 11, 2021, some 3,187 people died in Israel of COVID, the Health Ministry reported. Of those, 2,019 were unvaccinated, 284 were fully vaccinated and 884 were partially vaccinated.

“Proportionately, you see more unvaccinated than vaccinated people dying,” Maor said, adding that this is also the case with serious cases – the outcomes of the non-vaccinated patients are much worse than those of the vaccinated.

“The vaccines for variants usually provide at least partial protection,” Maor said. “They may not stop the pandemic, but they are extremely important for saving lives.”

To make the vaccines most effective, people will need to get booster shots.

“Why the big surprise?” Landsberger asked.

The Pfizer vaccine continues to prove itself between 80% and 90% effective against the Delta variant for those who got their shots in the last couple of months. Most of the breakthrough cases are striking older people who were inoculated more than six months ago. This means that the vaccine’s effectiveness waned over time.

This is somewhat expected. Most vaccines are given three, four or even five times, because it takes the body time to produce resistance. The hepatitis B vaccine requires three doses. A tetanus shot is generally administered about every 10 years. And a flu shot is required on an annual basis.

How often will it be between COVID boosters?

“We don’t know yet,” said Landsberger. “Probably everyone will need a booster six to 12 months after their first two shots and then maybe once every year or maybe every 10 years – but probably somewhere in the middle.”

While there were those who hoped that modern technology and the rapid pace of coronavirus vaccine development and administration could shorten the length of this pandemic – and it might – at the same time, the modern world is very small and travel is common, which could make stopping the spread of the virus even harder, Maor said.

“What are we looking for? Complete eradication of disease? Or are we looking for a state where we can return to normal life?” Landsberger asked. “I think the measure is not going to be a lack of disease but a return to our normal social and economic existence.”

Pandemics don’t just end. They fade into the background either when everyone is vaccinated or recovered or when society determines that they are no longer going to have a significant impact on people’s lives.

“The vaccine will be updated and it may be able to better deal with new variants,” Landsberger said. “The disease will get to the level where people are not frightened by it.

“But it is not going to disappear.”•