If a “dirty bomb” explodes in a crowded urban area, civilians would be at risk of exposure to potentially lethal levels of radiation. Accurate and rapid assessment of the elements used and the dose of radiation received by each individual would be vital to reducing damage and anxiety.

A dirty bomb, also known as a Radiological Dispersal Device (RDD), combines conventional explosives with radioactive material. Experts say the chance of one detonating in a crowded place is becoming increasingly likely.

An unlikely team is working on a solution.

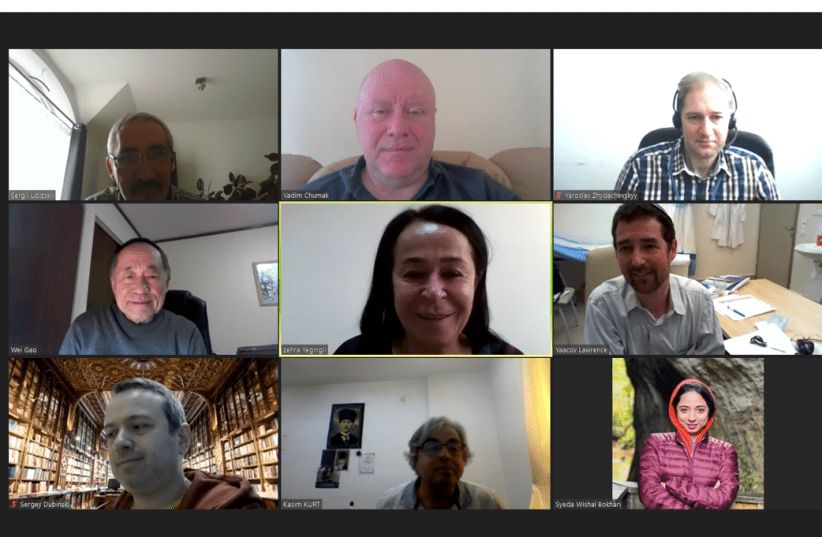

An Israeli radiation oncologist from Sheba Medical Center in Tel Hashomer has partnered with a group of other doctors and scientists from Turkey, the US, Ukraine, Poland and New Zealand to develop a small and cheap “dosimeter” – a badge that detects and measures exposure to radiation – for use in the event of a radiological emergency, specifically in urban settings.

To date, most efforts in this area have focused on merely quantifying a personally absorbed dose. This device would likely identify a single or any combination of radioactive contaminants in a short time.

According to the team’s report: “Such a device will not only fulfill an unmet need in homeland security but is also expected to attract significant commercial interest.”

The team was paired together through NATO’s Science for Peace and Security Program. Israel is not a member of NATO but is considered a partner nation.

“The idea of this ‘science for peace’ thing is that different countries work together on projects that are science-based but also have a military or anti-terrorist spin on them,” Dr. Yaacov Lawrence, vice chairman of Sheba’s Radiation Oncology Department, told The Jerusalem Post.

The final product is expected to look like two small sugar candies composed of various composite materials that absorb radiation or remember exposure to radiation, he said. After an event, these “candies” can be read by a dosimeter that the team is designing. The more radiation, the more the candies will glow after being activated.

The two types of candies are made of different substances, and each one will react slightly differently to the reader, indicating what type of radiation the person was exposed to. Such material could be sewn into fabric or a soldier’s uniform, for example.

Within the consortium, every country and lab has a different role, Lawrence said. In Turkey, Ukraine and New Zealand, they are synthesizing the materials; in Poland and Turkey, they are making the reader, he said.

Doctors at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia and at Sheba are working to understand the radiation and medical implications. The samples were sent to the hospitals and irradiated with a wide range of photon and electron beams.

“As a result of the project, I have developed close working relationships with colleagues in Turkey, Ukraine and Poland – a really quite unexpected development in my life,” Lawrence told the Post.

He said he hopes to visit his colleagues when the COVID-19 pandemic further subsides.

The goal is to complete the project in 18 months and to have a dosimeter suitable for commercialization, he said.