The author, the distinguished Australian academic, Suzanne Rutland, has been meticulous in her research to paint a recognizable portrait of Leibler, a large-as-life maverick who followed his own political path.

Leibler was fortunate to escape the Nazi embrace and sailed on one of the last ships out of Antwerp. Leibler came of age in Bnei Akiva and adhered to the National Religious camp throughout his life. He operated as a Jewish diplomat within the parameters of traditional organizations.

Leibler originally favored a life in academia, but was forced into running his family’s diamond business at the age of 23 when his father suddenly passed away. His father’s influential contacts and his business acumen however were inherited by the son — and thus provided the foundation to develop not only his own independent diplomatic initiatives, but also to rebuff the powerful and the corrupt with moral conviction. For some, Isi Leibler is a right-wing member of the awkward squad, for others, a stalwart who stood on principle and refused to budge.

One example of this was his early involvement with the cause of Soviet Jewry and “the office with no name” (Nativ). This had been established by Mossad founder Shaul Avigur in 1952 and led by Nehemiah Levanon, Zvi Netzer and Yaka Yannai in the 1960s. Australia’s campaign for Soviet Jewry remarkably preceded that of both the US and the UK. Indeed Australia’s UN representative, Douglas White, first raised the question of human rights for Soviet Jews as early as November 1962.

Despite his affinity for conservative politics and his support for Australian involvement in the Vietnam War, Leibler astutely cultivated skeptics within the local Communist party. After the Doctors’ Plot, the Soviet revelation of Stalin’s crimes and the invasion of Hungary in 1956, Leibler understood that there was a deepening ideological unrest in many Communist parties - and acted upon his inclinations. He showed them Trofim Kichko’s Judaism without Embellishment, published by the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences in 1963, which depicted crude images of hook-nosed Jews dipping their craw-like hands into pots of gold coins.

Leibler’s diplomatic initiatives on behalf of Soviet Jews took place in many unusual arenas rather than in the spotlight of grassroots activism. He conformed to the Nativ line and coordinated with Levanon and Netzer rather than with their critics in the Diaspora. This informed his public espousal in opposing the boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics even though US president Jimmy Carter had called for it as did the Australian prime minister, Malcolm Fraser, albeit privately.

Leibler conducted meetings with Soviet officials at a time when there were no diplomatic relations between Israel and the USSR. He struck up a relationship with George Zoubkov, vice president of the Soviet travel agency Intourist, through his own business interests. Zoubkov spoke fluent Hebrew and had been stationed at the Soviet Embassy in Tel Aviv between 1948 and 1953.

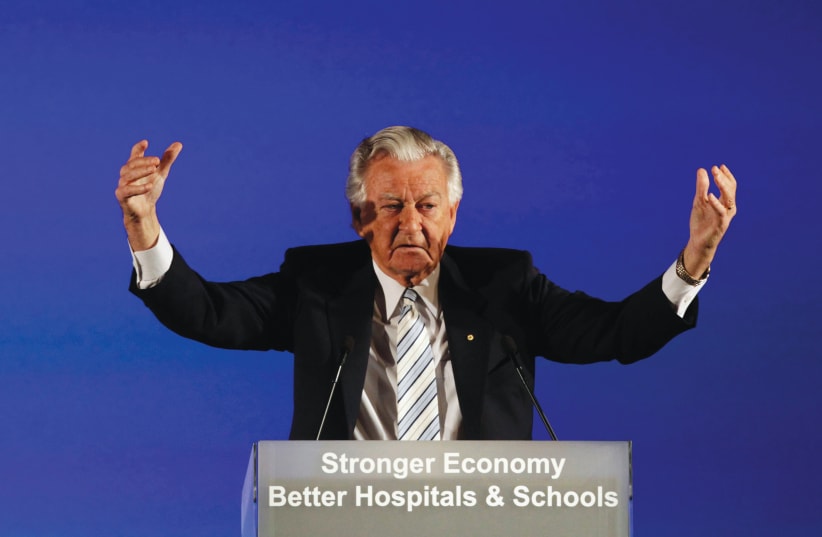

Leibler’s close association with Australian prime minister Bob Hawke led to several well-intentioned, but ultimately failed, endeavors to help Soviet Jewry. Hawke met leading refuseniks in Moscow and later wrote that “their nobility of spirit overwhelmed me... they were pariahs in a squalid society.” Following Mikhail Gorbachev’s ascent to power and the proclamation of Glasnost and Perestroika, Leibler used his contacts and his philanthropy to nourish the green shoots of Jewish life that had begun to appear in the late 1980s.

Leibler found it difficult to maintain good relations with Hawke and Soviet Jewry activists such as the late June Jacobs in London because they were doves when it came to the policies of the Begin and Shamir governments in Israel. Like many of his generation who followed Yosef Burg and the National Religious Party, he also found the messianic fervor of the succeeding generation perplexing and spoke about “an evil cancer that has invaded the religious Zionist camp.” He was thereby hard-pushed to adapt to the shifting sands of Israeli politics.

Leibler was devastated by the killings of Palestinians in the Sabra and Shatilla camps in 1982, but there is no mention of any endorsement of Israeli president Yitzhak Navon’s call for an inquiry — the Kahan Commission. Throughout the debacle of the Lebanon war, he reacted to the hostile media in Australia rather than to the issue itself.

For Leibler, this was a period of uncertain transition. He congratulated Yitzhak Rabin and welcomed the Oslo Accords, but then became disillusioned while Palestinian Islamists undermined it. On the one hand, he admired Amos Oz and brought him to Australia, on the other, he labeled Peace Now as “ratbags.” Meeting Palestinian Authority leader Yasser Arafat in 2000 was paralleled by supporting Ariel Sharon in the 2001 election for Israeli prime minister.

There is an absorbing chapter about Leibler’s bitter confrontation with Edgar Bronfman and Israel Singer at the World Jewish Congress (WJC). The author, Suzanne Rutland, comments that “Singer had plenty to cover up — for instance, a secret Swiss bank account, millions of dollars in WJC funds which disappeared, hundreds of thousands of dollars in unauthorized credit card expenditures and unauthorized transactions, salaries, pensions and cash payments and withdrawals.”

Freedom of Information requests eventually discovered a vast misappropriation of funds. Leibler had been right all along and Bronfman eventually turned against his long term protégé, Singer, whom he had hitherto regarded as a valued colleague. Bronfman dismissed Singer while refusing to file a police case against him. Bronfman made up with Leibler shortly before his death.

Ostensibly, Rutland’s book is a biography of Isi Leibler. But it is far more — a documented recent history of the Jews of Australia, a history of the political struggles of immigrants and survivors.

The writer worked in the British campaign for Soviet Jewry between 1966 and 1975.

LONE VOICE

THE WARS OF ISI LEIBLER

By Suzanne Rutland

Gefen Publishing

680 pages; $39.95