There is a common proposition that dehumanization leads to disengagement of moral restraints and is a precursor to mass violence. A new study proposes empirical evidence for this idea with an analysis of antisemitic Nazi propaganda.

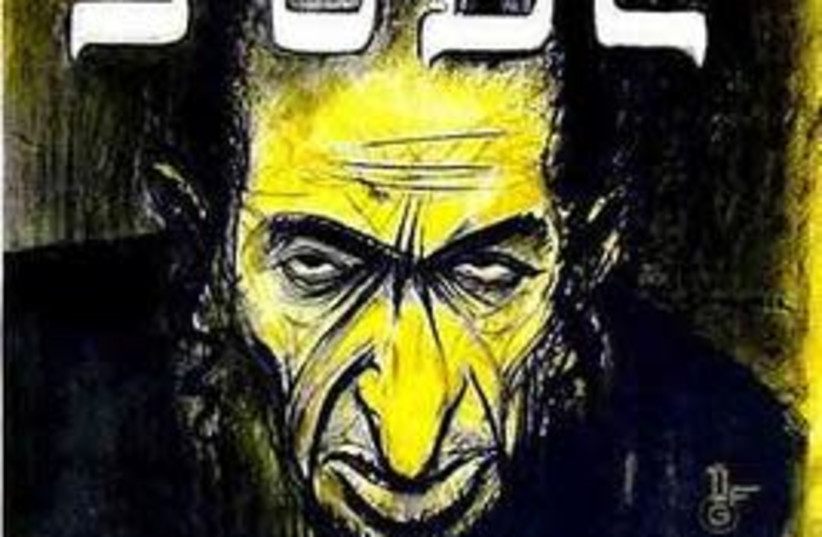

The idea is that dehumanization promotes violence by removing moral inhibitions against harming fellow humans. The antisemitic propaganda leading up to the Holocaust increasingly denied the Jews’ capacity for experiencing fundamental human emotions and sensations.

A linguistic analysis of Nazi propaganda was conducted by a team headed by doctoral student Alexander Landry of the Stanford Graduate School of Business in California and published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE under the title: “Dehumanization and mass violence: A study of mental state language in Nazi propaganda (1927 to 1945).”

Nazi propaganda that Jews can't feel emotions

The researchers analyzed hundreds of posters, pamphlets, newspapers and political speech transcripts from before and during the Holocaust.

They also assessed the prevalence of certain terms related to mental state, distinguishing between those associated with capacity for “agency” (the idea that people make their own decisions and are responsible for their own actions, such as “plan” or “think”) and those associated with experience such as “hurt” or “enjoy.”

Propaganda during the Holocaust increasingly used language related to intentionality and malevolence, suggesting that Jews were portrayed as possessing a greater capacity for “agency.”

The researchers speculate why this shift took place; perhaps it served efforts to portray Jews as a masterminding threat, while also providing rationalization to soothe Nazi executors who were traumatized by their experience of killing Jews.

Overall, suggested the Stanford researchers, these findings suggest that the dynamics of dehumanization associated with mass violence may be nuanced and shift over time.

The authors noted that their analysis included limited data for some time periods, especially in the months preceding the onset of the Holocaust in July, 1941, and that only one researcher was involved in drafting data collection guidelines.

Future research could address these limitations and further examine the dynamics of dehumanization for both the Holocaust and other genocidal contexts, they wrote.

“To eliminate violence, we must understand the motives that drive it. To do so, we examined the portrayal of Jews in Nazi propaganda. We found that Jews were progressively denied the capacity for fundamentally human mental experiences leading up to the Holocaust, suggesting that dehumanization can motivate violence by reducing moral concern for victim groups.”

Study authors

The authors concluded: “To eliminate violence, we must understand the motives that drive it. To do so, we examined the portrayal of Jews in Nazi propaganda. We found that Jews were progressively denied the capacity for fundamentally human mental experiences leading up to the Holocaust, suggesting that dehumanization can motivate violence by reducing moral concern for victim groups.”