Non-fungible tokens (NFT) are everywhere. You can’t scroll a news feed or website without seeing some celebrity or “artist” touting the latest NTF – a blockchain-based means to claim unique ownership of easily copied digital assets.

NFTs are a highly speculative purchase. The basis of the market is proof of unique ownership, which really matters only for bragging rights and the prospect of selling the NFT in the future. NFT mania arguably combines the most tawdry and avaricious aspects of collectibles and blockchain markets with celebrity culture.

And it is invading Israel at a rapid pace.

Last year, Shenkar College hosted Israel’s First NFT Conference. Among the speakers was Rob Anders, who co-founded Niio, an online platform that shares digital art, with Oren Moshe.

“A lot of the NFT artists,” Anders pointed out, “their dream is to be collected by real collectors and real institutions, not just a crypto whale who made a billion dollars.”

In a recent interview with The Jerusalem Post, he claimed that “most people who are buying NFT are motivated by a speculative interest” and predicted that “95% of NFT will be gone in two years.

“The two things needed in luxury [items] are scarcity and quality,” he pointed out.

The Transfiguration by Renaissance master Raphael, for example, has value. There is only one of it in the world, and it is the last work by a great painter. The gross misconception of NFTs as a virtual cat flying on a rainbow sold for a large sum of money (Nyan Cat, $590K, sale performed by the crypto art platform Foundation) is enabled because these two elements are now missing from the market.

NFTs can be understood as a linear progression within a mostly traditional art market. Collectors and dealers traded in paintings for centuries. Then, in the 20th century, video art, performances, installations and conceptual art all presented their respective merits and difficulties. A painting can be kept in a safe, moved outside a country or sold for quick cash.

The current NFT mania involves fantastic amounts of money. However, it must be noted that this money is almost always cryptocurrency. When a reader is informed US rapper Eminem (real name Marshall Mathers) bought the NFT Bored Ape No. 90555 for $450,000 last month the report is misleading. Eminem paid in Ethereum, not greenbacks. What he now owns is a virtual token of an avatar, nicknamed EminApe because its khaki and gold chain resembles what Eminem wears.

A lot of the hype around NFTs originates in social groups very different from those that artists tend to operate in – mainly cryptocurrency fans and those keen on libertarianism. This is because cryptocurrencies are not issued by a state, so people use them to buy and sell things without the state knowing. NFTs offer something to buy with a currency few people are aware of or even use. EminApe is only worth what Ethereum costs this very second. You cannot pay a mortgage with a cryptocurrency, no matter how hot it is at the moment. If Ethereum becomes worthless, no state bank will back it up.

So what does Eminem own? He has an electronic version of an image, which he is using for his Twitter profile. Other people are free to do the same. He has a record in a blockchain that shows he bought it. This is the token part in NFT. He also gets to be a member of the “Bored Ape Yacht Club,” a members-only online space whose benefits and purpose beyond being a marketing gimmick are unclear.

He is not entitled to any share of merchandising revenue from the character. He can profit from his purchase only if he can find someone else willing to pay even more for the NFT.

The rapper is not the only one who threw some bling at NFTs. Others include basketball stars Shaquille O’Neal and Stephen Curry, and late-night television host Jimmy Fallon.

These well-publicized purchasers effectively act as a form of celebrity endorsement – a tried-and-true marketing tactic. It is a graphic example of the power of media culture to stoke “irrational exuberance” in financial markets, especially during times when people turn to social media for “doing their own research” for anything from COVID-19 to how US democracy works. One survey in mid-2021 (polling 1,400 investors aged 18 to 40) suggested roughly a third of Gen Z investors regard TikTok videos as a source of trustworthy investment advice. A celebrity who speaks to millions of people via his or her social media can push prices way up.

Cryptocurrency markets, those who object to them warn, are a Ponzi scheme taken to the digital realm. For existing investors to profit, new buyers have to be drawn into the market. Remember the old Americanism about gullible people and the Brooklyn Bridge? You can buy an NFT of the bridge right now, CoinDesk reported last year. One NFT of the bridge cost 0.015 Ethereum ($26).

Unlike the price of bread, real estate or heating, the cost of an artwork is mostly determined by how much people are willing to pay for it. Lasagna on Heroin (2012) by Darren Bader, which at the very least is real and not an NFT, is worth as much as people are willing to buy it for. The Fountain by Duchamp, which is a plain old urinal, was sold for $1,762,500 in 1999.

If a person wishes to purchase a 10-second digital movie of, for example, a naked Donald Trump with the word “loser” written on his massive body for $6.6 million, he can. Created by US digital artist Beeple, real name Mike Winkelmann, such a work exists. It fetched this sum in 2021.

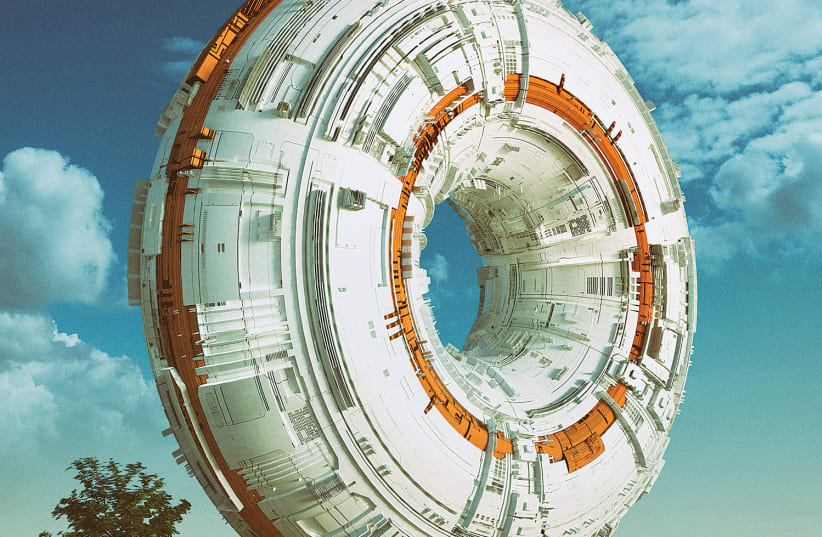

An Excerpt from the 2016 animation video Disco Beast by Jonathan Monaghan, one of the artists on Niio (Credit: Vimeo)

Or consider the 2016 computer-generated imagery (CGI) animation film Disco Beast by American visual artist Jonathan Monaghan, which featured the mechanical birth of a unicorn with jet wings as it soars from a coffee shop. How much would you pay to view such spectacular imagination?

SINCE THE 1935 publication of “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” by Walter Benjamin, art lovers and the market they inhabit wondered what the role of the real in art is. Benjamin warned that a real painting by, for example, Raphael or Durer, has a unique life force (aura) and argued that mechanically produced images lack it. It is important to note that “real,” in this context, does not mean the subject matter being depicted.

When Raphael painted Transfiguration in 1520, he did not look at an actual Christ floating in the air as a model. When Durer painted Charlemagne in 1510, nobody really knew what the Frankish king looked like, as he had been dead for 700 years. The artistic tradition of depicting things that are not “really there,” Frankish king or a flying unicorn, stretches back a very long way before Monaghan.

The NFT, in this light, is not a linear progression from objects possessing an aura to hard-to-sell ready-made objects like Duchamp’s urinal, conceptual art like Bader’s lasagna and the CGI video art of Monaghan. It is a replacement of human imagination (aura) with a digital token. What offers it value, in this electronic web of blockchain, is not the genius of the person who made it but how the token stands in relation to cryptocurrency and a market unmoored by either tradition or quality control.

As British art critic Waldemar Januszczak explained, fungible means exchangeable, non-fungible means all options to swap one thing for another are closed. What makes the 10-second video by Beeple unique is the token. Using blockchain, an unbreakable digital system issues a virtual token, securing that only this buyer (with the token) has a right to this video. Other people can take all the screenshots in the world; they do not own it, nor can they reproduce the film. There is no reel, no animation cells to be sold on eBay. When different persons outbid one another on the right to buy the token using cryptocurrency, the highest bidder will not get a diploma of ownership in the mail.

In his 2020 article, Januszczak explained that NFTs were all the rage in the NBA, where they served as a novel new collector’s item for sports fans, before they found their way to the art market.

“Few of these cyber-millionaires could tell the back of a Rembrandt from the front,” he wrote.

“What they wanted instead was poppy Internet imagery that reminded them of their skateboarding days and that time they earned a record number of hearts in The Legend of Zelda,” he said.

Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days fetched $69 million when it was sold at Christie’s, the third-highest sum paid for a work by a living artist. The other two artworks are by David Hockney, who calls NFTs ICSs for International Crooks and Swindlers, and Jeff Koons.

Udi Edelman, director of the Holon-based Israeli Center for Digital Art, points to what he considers a brilliant move by UK artist Damien Hirst, who currently offers the art market a choice. In his 2021 work The Currency, Hirst offers 10,000 paperworks that display spots. Each paperwork, sold for $2,000, is tied to an NFT. The buyer has one year to decide what he would prefer to have. If he opts for a nice paperwork to display at home, he loses the right to the NFT. If, on the other hand, he wants the NFT, the paper would be burned.

Writing for Artnet, Caroline Goldstein remarked a similar work on paper by Hirst fetched more than $393,065 in 2007. The floor price for an NFT work in The Currency series (at the time of publication) is roughly $28,500. The highest price so far, $120,614, was fetched for the NFT work Yes which is a part of this series.

“In this conceptual move,” Edelman explains, “Hirst lets the audience decide which technology would triumph here. He is finding out what people really want.”

AT THE Niio platform, Anders explains, “we fight back” against the NTF get-rich-quick phenomenon.

Founded before NFT became fashionable, the platform was built around the concept that “digital art should be as easy as digital anything – from wallet to wall.” Users can select a free option or a paid subscription. After they share what they usually enjoy in music or fine wine, the platform enables them to view a vast selection of works based on their existing preferences.

Monaghan is there, as is South African artist William Kentridge. A user could, for the sake of argument, borrow Disco Beast for a limited time and screen it during a special event.

A user might, for example, purchase an NFT based on a video artwork by Israeli artist Nira Pereg (her video art is on Niio, but no NFTs had been produced at this time). That NFT could be sold directly to another user on the platform in a private sale, or removed from it and kept in a private collection. Airports with a Niio subscription could project artworks at private jet terminals; luxury hotels might offer curated digital art displays to their guests; or a city could project curated works in public spaces. Braverman Gallery, which represents Pereg, is just one of the established art institutions users can find on Niio.

“We need a meaningful digital experience which is as easy to access in the click of a button as any other social media,” Anders suggested. “People need spaces to experience art.”

While searching on Dissrup (a digital art platform created by Yam Ben Adiva), I chanced upon an NFT work by LIŔONA (Liron Eldar-Ashkenazi), an Israeli designer and artist currently living in Los Angeles.

Her NFT Synth#boi (cocreated with Love Hultén) fetched 16 ETH (Around $ 51,715). Another work, The Muse of Time, by Or Yogev and Kaan Iscan, fetched 0.5 ETH ($1,578). Other works by Yogev, such as Sun Venus and Metavese Venus, are still up for sale.

“There is a tendency [among artists] to be wary of what is currently taking place in that market, as NFTs are not regarded as art-related but commerce-oriented,” Ben Adiva told me.

“It is seen as a creation of a different sort of beast, with the intention to flip it and make a lot of money. Artists who have a real-world presence are fearful of setting foot into NFT because of this bad image; and what we are trying to do [at Dissrup] is to build this world of digital art,” he said.

“The way the market is currently constructed scares artists,” he argued. “It is like a town square with everybody screaming, only on Twitter.

“Lots of artists think NFTs are about taking something you already did and putting it in a digital format,” Ben Adiva said. “This is not how it works. You need to build a community and communicate with it over time. You need to start selling at a low price and slowly raise the price for your artworks. You will not make a killing on a piece if nobody knows who you are.

“We help artists from the old world avoid mistakes on their path to this new one,” he concluded.

Recently, a painting by David Reeb that depicted ultra-Orthodox men praying at the Western Wall with the words “Jerusalem of Gold/Jerusalem of S***” painted on it caused such an uproar it was removed from an exhibition at the Ramat Gan Museum of Israeli Art. Speaking with Haaretz’s Naama Riba, Reeb said that “the fact people tell me: ‘Kol HaKavod’ does not translate to money. I do not need the entire discourse around this thing.”

In context, Reeb meant to defend his politically oriented art. Yet, if we consider his statement, we might find ourselves wondering. If hearing “Kol Hakavod” does not translate into money, what would happen when Israeli art attempts to go digital – and get paid?

While watching Yogev’s Venuses rotate on the screen, a sleek digital reference to the Venus of Willendorf and other prehistoric fertility figures, I wondered whether perhaps the digital could be the gate Israeli art must pass through to become more fun, more exciting, maybe even more popular.

“There will be plenty of Israeli artists who will try this path [of NFT],” Edelman said, “because this will be an easy way for them to reach an international audience. Will they succeed? Only time will tell.”

Reuters contributed to this report.