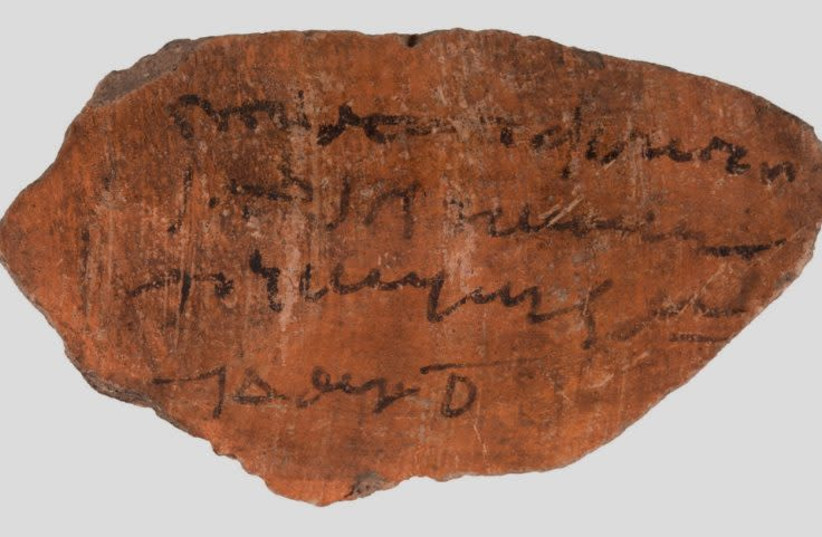

For the thousands of ancient texts discovered, scholars must devote countless hours in deciphering faded writing, filling in missing characters and sections of texts and determining the age and origin of the text.

Normally, epigraphers – scholars who study ancient texts written on durable materials such as stone, metal or pottery – use their own knowledge of repositories of information and digital databases performing “string matching” searches to find textual and contextual parallels. However, differences in the digital-search query that can exclude or conceal relevant results and that the texts often are discovered not in their original context can complicate the work.

In a new research paper published in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Nature, Thea Sommerschield, a historian and Marie Curie fellow at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice and a fellow at Harvard University’s Center for Hellenic Studies, and Yannis Assael, a research scientist at Google’s artificial-intelligence research lab DeepMind, presented their Ithaca state-of-the-art AI technology.

Ithaca is the first deep-neural network meant to improve the task of restoring and attributing ancient texts. It uses deep learning for geographical and chronological attribution for the very first time and on an unprecedented scale, the researchers said.

An AI deep-learning model is based on a neural network inspired by the biological neural networks we have in our brains, which can discover and utilize complicated statistical patterns in large amounts of data.

Recent increases in computational power have enabled these models to tackle challenges of growing sophistication in many fields, including the study of ancient languages, the researchers said.

“We have trained computers to use these neural networks to learn from masses of data, so that they may apply what they have learnt to new data they haven’t seen before,” the researchers said in an email. “This is the architecture embedded in the code behind Ithaca’s interface. One can use this model for your own research as an historian, by inputting the text you wish to restore, date or place and asking Ithaca to provide you with prediction hypotheses.”

Ithaca is trained on the largest dataset of ancient Greek inscriptions and across the ancient Mediterranean world between the seventh century BCE and the fifth century CE, the researchers said. These texts were chosen because of the varied contents and context already existing for them and because of the available digitized database for ancient Greek, they said.

Ithaca is meant to be a collaborative technology, focusing on collaboration, decision support and interpretability, the researchers said. While Ithaca alone achieves 62% accuracy when restoring damaged texts, combining it with the use by historians improved the results’ accuracy from 25% to 72%, they said.

“Ithaca can attribute inscriptions to their original location with an accuracy of 71 percent and can date them to less than 30 years of their ground-truth ranges, re-dating key texts of Classical Athens and contributing to topical debates in ancient history,” they said in the report.

Ithaca includes different visualization aids to increase the ability of researchers to interpret the results, allowing them to evaluate multiple possibilities. This could help historians increase precision by narrowing the wide or vague date brackets they must sometimes resort to, the researchers said.

“These visualizations allow experts to use their contextual knowledge to choose the best-suited output and may shed light on unexplored historical insights,” they said.

Their research shows how models such as Ithaca can “unlock the cooperative potential between artificial intelligence and historians,” impacting the way one of the most important periods in human history is studied and written about, they added.

They conducted an extensive case study on some Athenian decrees from the time of Socrates and Pericles to test the system. Historians currently disagree on the dates these decrees were made. The decrees have long been thought to have been written before 446/445 BCE, but new evidence suggests a date of the 420s BCE.

“Although it might seem like a small difference, these decrees are fundamental to our understanding of the political history of Classical Athens,” the researchers said in their email.

Their training dataset contains the earlier date of 446/445 BCE for the decrees, and to test Ithaca’s predictions, they retrained it on a dataset that did not contain the dated inscriptions and then submitted these texts for analysis.

“Remarkably, Ithaca’s average predicted date for the decrees is 421 BCE, aligning with the most recent dating breakthroughs and showing how machine learning can contribute to debates around one of the most significant moments in history,” the researchers said.

Ithaca’s architecture makes it easily applicable to any ancient language, including Latin, Mayan and Hebrew, and to any written medium, including papyri and manuscripts, they said.

The researchers said they are currently working on versions of Ithaca trained on other ancient languages. Historians can already use their datasets in the current architecture to study other ancient writing systems, including Akkadian, an ancient Mesopotamian language; Demotic, an ancient Egyptian script; and Hebrew and Mayan.

“We’re really excited to see the new directions Ithaca will take – and for this reason, Ithaca’s is open-sourced and available online,” they said. “We do see a lot of potential in interdisciplinary research on AI for culture and humanities.”