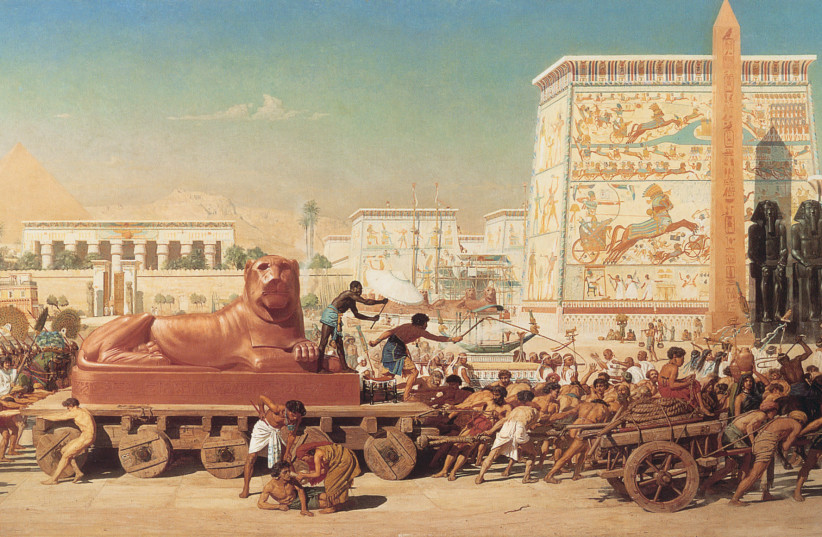

Over the past few weeks, millions of Jews gathering in synagogues all over the world have been reading about the Exodus from Egypt, one of the founding moments of Jewish history and identity through the millennia.

Bible scholars and especially archaeologists, if not most researchers, though, are skeptical that the narrative reflects historical events with any accuracy. They point to the lack of archaeological evidence in Egypt or in other locations mentioned in the story, as well as to the lack of records outside the Bible itself.

However, according to Prof. Joshua Berman from Bar-Ilan University’s Zalman Shamir Bible Department, some of his colleagues are making a fundamental mistake: They are looking for evidence of the Exodus in Egypt, instead of looking for marks of Egyptian culture in the Torah, the Five Books of Moses.

“The Torah is infused with Egyptian culture and its response to it,” Berman said.

“What I find incredibly fascinating is how familiar the Torah is with Egyptian culture, suggesting that the Israelites were indeed in Egypt, and they were there for a long time, but also that the way the Torah engages with this material is what today we would call cultural appropriation – a people using the propaganda of their oppressors and making it their own,” he said.

“The Lord freed us from Egypt by a mighty hand, by an outstretched arm and awesome power, and by signs and portents,” reads a verse in the book of Deuteronomy describing the Exodus.

The expression “mighty hand and outstretched arm” appears multiple times in the Bible, but only in the context of the Exodus. Berman said this is not by chance, as these praises were used in Egypt as well.

“When we look at inscriptions from the period of the New Kingdom, between 1500 and 1200 BCE, roughly the period of the enslavement, these expressions are routinely used to describe Pharaohs and their victories in battle, for instance, ‘Pharaoh defeated the Lybians with a mighty hand,’” he said.

The image was employed to refer to Pharaoh in that specific time. That makes it unlikely the Israelites or a more recent biblical author would have been aware of it centuries later, Berman said.

ANOTHER ELEMENT to support Berman’s theory is a bas-relief depicting what was considered the greatest achievement of Ramses II, the battle of Kadesh, where he scored a huge victory against the Hittites in what experts describe as the greatest chariot battle in history. Ramses II, who reigned in the 13th century BCE, is thought to have been the king of Egypt featured in the Exodus. The bas-relief was carved in the temple dedicated to the pharaoh in Abu Simbel, near the border with Sudan.

“After his victory, images of his war camp appeared all over Egypt,” Berman said. “At the core of it, there was his throne camp, made of two chambers, including a smaller one where Ramses himself would sit.”

“What scholars have noted is that the left chamber has the dimensions of two to one, and the right chamber has the dimensions of one to one,” he said. “Those are exactly the dimensions of the Tabernacle in the Torah.”

The Tabernacle is the portable sanctuary built by the Israelites during their wanderings in the desert, as described in the Book of Exodus.

“The claim is that it was modeled after Ramses’s battle camp,” Berman said.

Another connection between the battle with the Hittites and the history of the Exodus was that the Hittites are depicted as escaping into a river.

In addition, after the victory, Ramses’s troops sing a song of praise dedicated to him.

“In the Exodus, the Israelites also sing a song of praise to God, and the words are very similar,” Berman said. “For example, Ramses is described as consuming his enemies like chaffs, like straw, and the Israelites also say that God consumed their enemies like chaff. There are no other texts featuring this image in the ancient Near East.”

The use of names of clear Egyptian origin in the Torah also suggests the close connection with Egyptian culture, he said.

“Miriam, for example, means ‘beloved of the God Amun,’” he added.

Regarding the absence of evidence of the enslavement and escape of the Israelites in Egypt, Berman said the Egyptians never recorded defeats and negative moments, “in the same way today nobody writes on their resume that they have been fired.”

It is true that many researchers do not believe the Exodus happened, but many others fully support the notion that it did, he said, adding that very often these two schools also reflect different political beliefs.

Berman said while it is true that many researchers do not believe the Exodus happened, there is also a vast camp who fully support the notion that it did. He added that very often these two schools also reflect different political beliefs.

He has personally been researching the topic for the past 10 years.

Last year, he was finally able to fulfill his dream of visiting Egypt and the different sites bearing evidence of what he learned.

On Monday, he set out to Egypt once again, leading a special 10-day kosher trip to visit the same sites.

“I thought it would be cool to bring religious Jews to see where their forefathers were enslaved,” he said ahead of the trip.